Logics and the vocation of the Latin American territory of the last decades. Get to know the political context that gives rise to a new moment and a new political identity that seeks to strengthen identities, rights and democracy.

To begin to enter into this possible alternative story about Latin America, we have to tell some of the old and not-sowell- known history. The aim of this chapter is to present a more subjective version of this past, that can help us understand why it is within this outdated and backward context that new possibilities and dreams for collectivity are emerging.

Perhaps if we read this history that is made up of so much pain and loss of life through a more generous lens, we will see that it also shaped a resistant, persistent and creative people.

No system is so perfect and closed that it doesn’t have some cracks, out of which revolutionaries and disruptors can emerge, grow and flourish.

Given the many encounters of peoples and the richness of beliefs and rites, one cannot understand Latin America without drawing on the region’s imagined personalities, scenes and on what has happened throughout time.

We are woven from many colors, textures, scents, flavors and rhythms.

This report is about this land and these people. Before it became a reality and before any of us were here, Latin America was an invention of many imaginations coming together.

Many have fought over what the destiny of this land would be. We are the stage for the world’s imagination, as well as for disputes, wars, violence and authoritarianism.

Our people have been living in the crossfire for a long time, whether from the violent process of colonization or from groups of people whose allegiances were not as intractable as they seemed.

As such, on one side we have those who concentrate power among a few, and on the other we have those who dream of a democracy capable of liberating each and every one of us.

Take the example of Canudos: a city independent of nation, that was born within the imagination of a people and founded in the middle of the desert, never being allowed to come to fruition. Or many others – Zapatas, Allende, Guevara – who disputed and dispute this history.

The forms of state violence that occupy territories today were first constructed in opposition to “imaginings” like these. Today, this violence holds citizens hostage to a new story of a democracy; one which is exercised through institutional, patriarchal and controlling politics

Disimagination takes away the rights of individuals to craft new realities.

It is a logic of power that appears in repressive actions, be they ideological, physical, institutional or political, that impede us from imagining and exercising collectivity.

Disimagining in politics is the process of no longer dreaming, thinking and constructing the collective. Not understanding politics as a tool for transformation, little by little, Latin Americans also stopped believing in a connected territory and identity.

Fragmented society

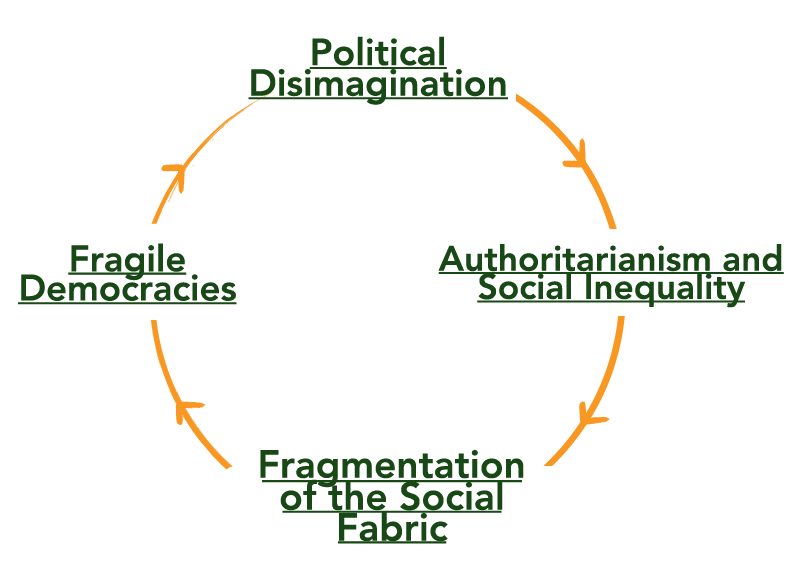

This logic produces a fragmented society, a reflection of an unaccessible state.

Divided by an “us vs. them” logic, we shy away from the idea that it is possible to build a society around diversity.

This system follows a “divide and conquer” strategy, taking control and power through fragmentation and making it more difficult for smaller groups to come together.

The result of this process is the isolation of groups and individuals as unsewn scraps of the social fabric.

Latin America is a fragmented continent, from the physical form all the way to its thinking.

Ginna, Colombia

The social fabric is the interaction among different social units, such as families, communities and institutions, and the individuals that comprise them. The relationship among these units is what gives society its form.

A healthy social fabric facilitates trust and care among individuals who share a common identity, such as culture or history, and builds structures that allow for collective decision making.

A lot of what happens today has to do with to the lack of a social fabric. There are many factors that explain this: from the fact that civic education is no longer in schools to the fact that society is completely contaminated by consumerism and individualism. I feel that a large number of the problems and conflicts that we have today, on a political and social level, have to do with our lack of knowledge about how to construct a social fabric.

Juan, Chile

– A different Latin America seems unreachable because we are systematically prevented from imagining it.

How is this logic sustained?

Political disimagination is sustained through two interconnected pillars, which can be observed throughout our recent history.

visible & invisible

as behavior control

The result is an inadequate

democracy that is only for the few.

The emerging political imagination

A combination of historical factors creates conditions in which the Latin American political imaginary can be restored.

Military dictatorships defined Latin America in the 50s and 60s. The democratic revival came in the 80s and 90s. Despite its superficiality, the democratic system opens space for political imagination.

With the widespread access to the internet, society has tested the limits of democracy, pushing for it to update and respond to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

Between 1979 and 1990, more than a dozen Latin American countries experienced a democratic transition. Part of the motivation for this came from the global economic context, as neoliberalism and globalization are incompatible with nationalist and authoritarian military regimes.

Citizens also fought for democracy in their countries. The journey towards democratization involved struggles, setbacks, advances, tensions, resistances and negotiations that continue today and that must continue into the future.

A democratic system was implemented without the adoption of a democratic culture and or a change to the old logic. The result is that elites maintain their status and privileges in a democracy that is still restricted to the few.

It has been thirty years since we brought democracy back and, still, democracy can’t address the simplest issues of citizenship.

Margarita, Argentina

I believe that the transition from a dictatorial system to a democratic system is a very significant change, both in the quality of my citizenship and in how I conceive of my citizenship in relationship to my interlocutor, who is supposed to represent me. We have to stop acting like adolescents who complain about everything and become adults who say: we really have to let go and sacrifice certain things, renounce other things and make decisions.

Pablo, Chile

Without adopting a democratic culture and its principles, democracy in the region is restricted to election season. Elections are presented as the material evidence of the democratic system.

The desire for political participation beyond elections and for a democracy that can overcome old habits are part of the maturing process of the system and, of course, of its citizens.

The nation-states are very limited. In other words, we are from the West, but we have a modernity that I call ‘unfinished modernity’. There was no system of distribution of rights throughout society. And so both modernity and democracy are very limited. They leave out black people, indigenous people, women, and young people.

Matias, Argentina

Digital networks bring back the possibility of imagining a different future. This can mean political action in which citizens discover their own voices and echo others, organizing around new themes with a logic of collaboration.

We update democracy through the use of networks and information technology as tools for citizen participation.

Juan, Mexico

I cannot think of an active citizen or of politics without technology. It is a way to make information more readily available and to construct narratives in spaces that were previously very monopolized.

Cecília, Brasil

The audacity of the youth acting in a fearless, direct and transparent way surprises government officials and creates a powerful wave that reverberates on the streets and on the internet.

In 2011, the organized university student movement goes to the streets to protest the higher education system. This moment inspires other movements, such as the Revolución Democratica, Autonomistas and Esquerda Autónoma, and gives rise to three leaders, who were elected as independent candidates to the Federal Congress. The movements from which they came organize into political parties and, in 2017, construct the “Frente Amplia de Esquerda,” which elects 21 representatives, 20 congressmen and one senator, as well as supporting presidential candidate Beatriz Sanches, who comes in third.

The student movement “Yo soy 132/I am 132” arises in 2012, after university students impede a visit by the thenpresident Peña Nieto. When he counterattacks, saying that their demonstration had been organized by the leftist parties, the students mobilize on the internet and bring thousands of people to the streets. This process helps sanction a political reform that allows for greater political participation, providing for independent candidacies, for example. Wikipolitica then configures itself as a movement that supports independent candidacies and elects Pedro Kumamoto to congress in 2014. In 2018, he is running for senate.

In June of 2013, demonstrations against the rise in bus fares spread through the streets of Brazil’s major cities in an uprising that mobilizes all parts of society, not just the left. The unsatisfied right wakes up, too, making their own claims and demands. The impeachment of President Dilma in 2016 and the frequent cases of corruption reveal the need for national political reform and renewal. Movements like the Bancada Ativista in São Paulo and Muitxs in Belo Horizonte begin their work. Other renovation movements such as Agora, Acredito and Renova follow suit.

In response to a situation in which 70% of Uruguayans said they were in favor of the reduction of the age of legal responsibility, young students mobilize debates in the universities, at home and on the internet, creating the largest mobilization in the country. In 2014, they are able to block the measure, winning a huge victory for the movement and also strengthening civil society. They take advantage of the timing and mobilize to protect other civil rights, such as the legalization of marijuana and gay marriage.

In June of 2015, news of the murder of a fifteen year old girl in Santa Fé mobilizes people quickly on Twitter and escalates to the streets in an uncommon, organic way, bringing together more than 300,000 people from different social classes, ages and places to call for an end to femicide. “Ni una a menos/Not one less” also helps to pass Law 26.585, which protects the lives of women, as well as spreading the message throughout the country and region.

When the president decides to extract petroleum from the soil of the Yasuni park, which has the greatest biodiversity in the country and is an indigenous reserve, a movement of youth organized in many environmental collectives collects more than 800,000 signatures calling for a referendum that would impede the extraction of resources from the park. Even though the government does not approve the referendum and attempts to control the movements, the impact of this environmental and civic mobilization is huge, with society coming out in force.

After denouncing corruption involving the President and Vice President, civil society calls for them both to renounce their posts. This is important because it happens in a country with a history of violence, political persecution and armed conflict, a society that always lived in the shadow of authoritarianism. A Facebook event called RenunciaYA/ Renounce Now mobilizes 25,000 people and convinces the president to step down. This wakes a generation up to new ways to enter into politics. And this is symbolic, because these young people were raised in a country that that has long been afraid of standing out and occupying public posts. Their mobilization contaminates all generations of Guatemalan society.

In 2015, the government makes an announcement about the peace deal with the FARC while the opposition disseminates fake news and political propaganda. This polarizes society around a question that could not be simplified. The peace deal does not pass and young people, leveraging their sadness and deception, promote meetings and debates that end up concentrating in the Bolivar Plaza, headquarters of the central government. They occupy the plaza, putting pressure on the government to continue the talks. Because of this, the deal is maintained. Insurgence springs from young people who were previously afraid to become involved in politics. In this context, they began to converse, become involved and occupy politics to guarantee civil and human rights.

Through the 21F referendum, Evo Morales consults society about his fourth reelection. Young people speak out against the measure and prevent it from passing. They understand that despite the advances of his government, not holding elections presumes a dictatorial system. For them, the regular changeover of power is necessary. Yet again, the youth take the helm to resignify the democratic system and occupy politics. The movements FUR (a party that seeks to run candidates in 2019) and OTRA ESQUERDA POSSIBLE give rise to a new left that is seeking a more just democracy.

The elected president declares in his campaign that he will not run for re-election. However, at the end of his mandate, he makes a political and judicial arrangement to re-elect himself. This provokes a popular uprising in March 2017. Despite the uprising, the next day, the measure is approved. Thousands of people, representatives of all social classes, ages and genders go to the streets in a violent uprising against this move, causing the president to go back on his decision.

The rise of a new behavioral profile that shows a new way of thinking and doing politics in the latin american territories: its actions, strategies, principles and values.

The political innovation definition of this context and its main challenges. Know the tools that this ecosystem use to get stronger and transform institutions and society.