Constitutional Rights Lab

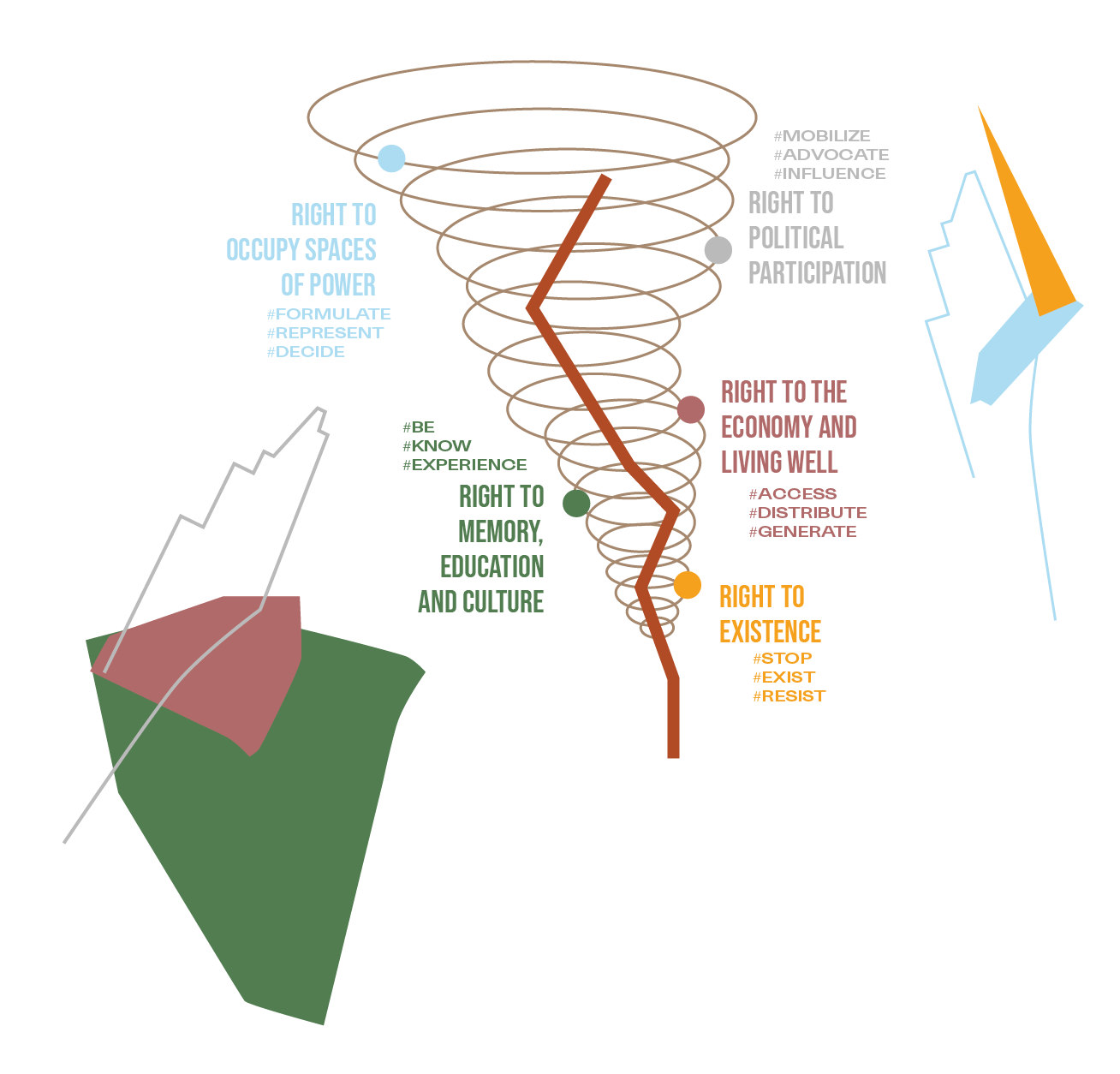

The doers rehearse a society. They put into practice and into the world solutions that promote access to basic constitutional rights and are constructed in relationship with their territories and their people.

Article 1. The Federative Republic of Brazil, formed by the indissoluble union of the states and municipalities and of the Federal District, is a legal democratic state and is founded on:

I – sovereignty;

II – citizenship;

III – the dignity of the human person;

IV – the social values of labor and free enterprise;

V – political pluralism.

Sole paragraph. All power emanates from the people, who exercise it by means of elected representatives or directly, as provided by this Constitution.

The peripheries are outside the structural and ideological reach of most public policies. The doers breathe life into these territories by building initiatives that seek to materialize foundational rights through cultural and social practices.

Given the proximity of spaces of elaboration and practice, solutions emerge that embody the dynamism of the peripheral reality rather than a distanced, stereotyped interpretation.

These practices come out of the territories and their knowledges and subjects. The process involves a constant cycle of creation, testing, and validation of solutions that can be reproduced throughout the city. As an alternative to social work, the doers create continuous experiments and research projects that go beyond practice to include efforts to exert political pressure and magnify what works.

It is in this context that the doers transform their territories into what we call Rights Laboratories. We chose this name because the solutions found are not frozen in time and space.

“From my point of view, the logic that we used when organizing the Image Workshops was always one of experimentation. All of our projects came out of experimentation processes, this is an innovation laboratory, what you call Social Innovation.”

Bernardo, Belo Horizonte

Political innovation in the periphery

“I tell stories from the ghettos of mundaréu

Where the winds make hills out of trash and pests lay their eggs.

I speak of people who always get the worst

Who eat the rotten parts and live on the margins of the river

And almost drown every time it rains

and whose cheers, never heard in the stadiums, don’t make a difference in the game.

I speak of people who make love in the narrow alleyways

Strange paths through the fields of bom deus.

I speak of these people who, despite everything, are generous, passionate

Happy and hopeful and who believe that existence is better

In Oxalá’s peace, if you want to know my name you don’t even have to

Ask, my name is…”

Cidade com nome de santo / City with the name of a saint / Rodrigo OGI

Peripheries are legitimate urban territories

Peripheries, favelas, settlements, ghettos

margins for whom? At the margin of what?

Representations based on stigma reduce peripheries both in the narrative and in the structure of cities, assigning them the leftovers of the dominant understanding of what comprises the city itself. A sociocentric logic has colored historical portrayals of peripheries, favelas, settlements and ghettos. They have not been considered part of the social fabric with their own identity, but rather have almost always been painted as a negation of what the central region, which is majority white and economically privileged, considers to be the norm.

“The periphery is politics, the periphery is struggle, it is resistance. The most important debates are coming out of the periphery. It is the people from the periphery, women, black people. The peripheries are the minority in terms of rights and the majority of the population. The politics of the future is in the periphery.”

Luiza, Recife

Public policies created without listening to and including people from the peripheries do not take into consideration the social dynamics and characteristics of these territories and thus do not meet real demands. This distorted understanding of peripheries and unwillingness to identify them as legitimate parts of the city causes two main delays. It perpetuates narratives that reduce, make inferior and criminalize the residents of the peripheries and it perpetuates a lack of understanding of priority and innovative public policies for these territories.

On the other hand, the segregation between the impoverished and the rich in the city is unilateral. The citizens with the most privilege do not move through the city. They do not know its full extension, its margins, its hillside communities. Citizens living in the peripheries, however, work, study and move through the entire city. They have been to other regions and are far better prepared for processes of interchange and sharing experiences.

Basic rights such as access to education, specifically to a university education, to non-precarious work and to basic sanitation are urgent issues for all Brazilians. In the peripheries, access to these rights is scarce. The few people that do have access perceive the way these rights can open the door for other rights and guarantees.

Political education from within the peripheries

Political articulations have historically been carried out within the institutions that entered the territories to work as organizers and mediators of peripheral political subjects and their sometimes contradictory or conflicting needs and diverse interests. In the 1980s, churches, school associations, unions and the grassroots arms of political parties were the principal spaces for political education. Starting in the 1990s, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) became the protagonists of political education in the peripheries.

“I came up in social projects. Here in my community, over there on the corner, we have a Protestant, Christian organization. They used to be much more social than religious. Today the question of religion is pretty annoying. But at this organization, I had the opportunity to try out woodworking, theater, English, guitar, swimming, tennis, dance, culture, sports and education. Even with the religious bent, it is what made me who I am today.”

Kadu, Belo Horizonte

The peripheries have changed socially, culturally and economically in the past 15 years. New arrangements for conducting political disputes and urban advocacy started to provide political education through autonomous cultural collectives, an activist presence and public policies for access to university. These efforts transformed not just the participating subjects, but also encouraged transformations in their families and their neighborhoods. This presented new possibilities for existing and occupying spaces in society, specifically with regard to the right to education.

The social dynamic out of which these peripheral subjects emerge also changed. They circulated in different social spaces and connected with different groups in the academic realm, expanding their repertories. Transformations also happened as a response to needs that arose in the peripheries and called for the invention of new strategies and tools.

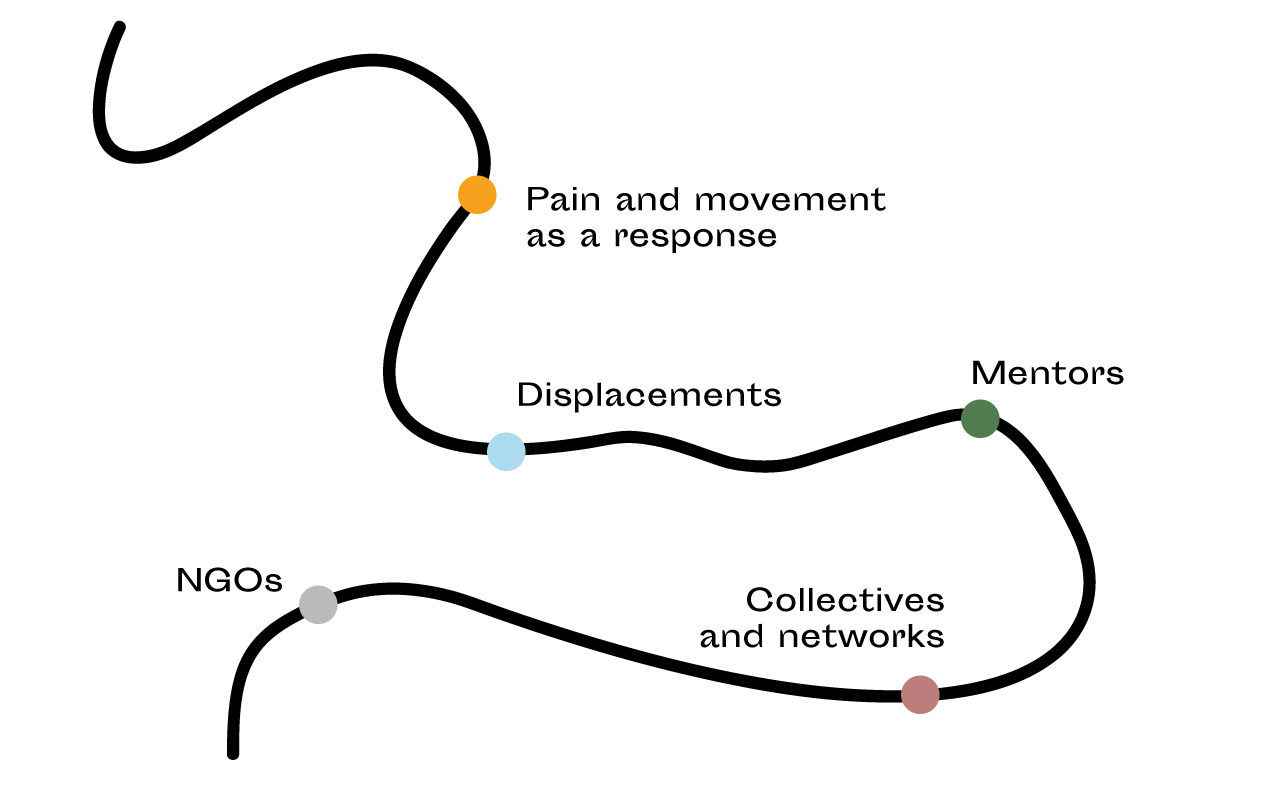

From the peripheries

In our research, we identified five contexts that awaken and mobilize political actors from the peripheries. Beyond understanding these actors as from or of the peripheries, we recognize that they work from the standpoint of the peripheries, circulating throughout, disputing and defining priorities for the political life of entire cities. They influence these large territories that include different visions, identities and complexities.

Peripheries to express plurality.

“The periphery is actually peripheries, with an “S.” Yes, we started to think about peripheries, within the peripheries there are many things that, like, here it is not the same as on Edu Chaves, which is another street nearby.”

Jesus, São Paulo

To describe this new political subject, we use the name fazedor (doer), a term that researchers who specialize in peripheral territories encountered and with which they identify. Much like the doers, there also exist producers, or weavers, as Instituto Update calls them, synonymous terms that define the behaviors that reconstruct the social fabric through citizen emancipation, collectivity and experimentation with new political practices. Since political innovation is plural and diverse, the language used to describe it can also be flexible and adapted for the particular reference and context.

It is not one periphery, it is all of them.

The plurality that infuses the doer’s discourse has a well-defined political objective.

The emphasis on peripheries reflects an effort to preserve the collective identity that gives doers a place and a perspective from which to fight in the world. At the same time, it points to and qualifies each territory based on its specific characteristics. This guarantees a right to identity in the territories as well as pressuring the state to be open to participation, to accept that people from the peripheries will occupy spaces of power and to consider the necessities and specific demands of the peripheries when crafting policies for the city.

Neighborhoods as subjects

Doers are products of their context. The social and cultural dynamics in their neighborhoods appear in and influence their practices. These new political subjects are a part of and also advance the collective identity of their territories in the urban imaginary.

Throughout the research, it was common for people to introduce themselves by saying their name and, immediately after, the place where they live. In some cases, the name by which a doer is known throughout the city contains their neighborhood.

“I go by the name Cris from Prazeres. Prazeres Hill is my home.”

Cris dos Prazeres, Rio de Janeiro

Pain and movement as a response

Pain is a structuring element of contemporary political subjects from the peripheries. It is inflicted through a series of continuous actions of state violence and structural racism and sexism.

Structural racism becomes institutional racism in the actions of state security forces, the lack of dignified housing and basic sanitation, and the lack of access to education and health, among others. It appears in human rights violations, including the right to life and to dignity. It leaves psychological and physical scars. It is negligence interrupting life. Someone should have been there to save these people, and they weren’t.

Violating the honor of a person or their collective when telling a story to the world criminalizes victims and stigmatizes the peripheries. After a traumatic situation, the subject intensifies relationships, seeking comfort or the creative strategies that do not repeat the trauma. This expansion of networks, repertory and connections boosts and projects the subjects as leaders who carry possible solutions.

“After he was attacked and he saw that there was no other way out, no other solution, he moved to a new city, to a new state, to a new life. And then I could see it. Before that, before everything that happened to him, I thought that people could not re-socialize. And seeing my brother’s case up close, seeing that he re-entered society, that he is another person, he is able to study, to work, to have a healthy social life, this impacted me and made me want to provide that for other people. Because that is a solution. A tragedy doesn’t have to happen for things to change. I think of grassroots education, public policies that help young people, so that they aren’t always marginalized, living at the margins of the law. I think that was a factor that got me more involved with social questions.”

Raquel, Recife

“I have made my rounds through the city working many menial jobs. This showed me that the world isn’t make believe and that the reality that I came up in is cruel, especially for black men and women, for groups that are outside what we can call the heteronormative, caucasian standard. People outside this white and heteronormative standard end up having many triggering experiences that inspire them either to fight or to adapt. I chose to fight and I am still fighting today.”

Álvaro, Belo Horizonte

“The gang rape of a young girl by 32 men moved the entire country, I think, and it moved us, too. And all of the noise made us come together, but then that same old story repeats. What now? We are going to get mobilized, protest in the streets and five days later it is all over. Can we do anything? Is it possible to do anything?”

Cíntia, Brasília

Displacements

When doers move beyond their original physical territories, they expand their understanding of inequality. It is in coming and going from other spaces that they understand how a cumulative denial of rights happens in the peripheries. Without access to education, memory and culture, a person will have little knowledge of how to access health, finances, well being and everything that comes after.

“The moment that woke me up was when I had the opportunity to work in an upper class place. I lived in São Gonçalo, a periphery of Rio de Janeiro, in a community called Menino de Deus, and I had the opportunity to work in the Rio de Janeiro South Zone, in Botafogo. At that job, I had the opportunity to have lunch. The company paid for the lunch and because I thought everyone there was rich, I imagined that the food would be spectacular. When I got there, I saw that the people had access to different foods than I did, which reinforced my thinking that their food was for rich people and my food was for poor people. At that moment I started to understand that I needed to break down these food questions for my community.”

Hamilton, Recife

In this moment, doers oftentimes feel the loneliness of insertion. They start finding it difficult to recognize themselves in their places of origin and, at the same time, they do not see themselves belonging to new spaces.

When the doers access other spaces where basic rights are guaranteed, moving through the city for work or study, a clash of contexts reveals different social dynamics from those present in their territories. Through analyses that mix estrangement with an ability to translate, they start work so that the rights that they identify in these new environments are also guaranteed in their territories.

The displacements are also intersectional and stimulate empathy, even if the doers come from different contexts of origins, race and gender.

“(…) it was after a protest organized by the group ‘React or Be Killed’ from Salvador, right after that mass killing in Cabula, where they executed 12 young people and the police officers basically did not go to trial and were acquitted. A friend of mine named Lúica, who is from the periphery, had invited me to go along. She said ‘come on, come see how it is for black people in the city.’ And I thought, well, I am black, but I am middle class and black. And so being in the peripheries, seeing that lifestyle up close, the violence was all far from my experience, I had not been close to it. ”

Thaisa, Recife

Mentors

Teachers, progressive religious leaders or educators in arts and culture classes. People recognized as mentors may occupy different social roles. When in contact with doers, they construct an environment of trust, exchange of references and expansion life skills and worldview. They fuel the construction of a critical outlook and point out pathways whereby doers can use their talents to transform reality. Provoked and instigated, the doers put themselves in motion to support their territories from within. This can happen with the orientation of a mentor or as doers construct their own path of research or action.

“I lived in Salvador for 16, 15, 17 years. A journalist named Márica Guena came back from Senegal and started a community newspaper in the ghetto where I lived, in the Beiru neighborhood. The paper’s mission was to stimulate debates around black affirmation and recognition, the valorization of black bodies and the black aesthetic, since Salvador is a city where more than 70% of the population is black. At that time, there were low percentages of black people in politics, in the media, in the big jobs at companies. There was also an effort underway to whiten us, our hair, our aesthetic and our music. And then when Márica came back to Salvador she perceived this and went back to the neighborhood to bring people together. This process led to the Beiru Community Newspaper Association. We stayed together there for over a year, I stayed for almost two years. It was a process that woke me up. I had never seen my ancestry before, had never recognized many issues related to my background. You know, my grandmother had a Candomblé terreiro and when she died, when I was 10 or 11, my family left that behind.”

Jesus, São Paulo

NGOs

NGOs are some of the of the most traditional spaces for the education of political subjects in the peripheries. They have had a marked presence in the territories since the 1990s. Many leaders who today are engaged in other forms of political and social organization in the peripheries, such as the collectives and networks presented in this research, came up in the NGOs.

Some NGOs have a strong socio-educational focus and have served as spaces for formulating and practicing citizenship. They give residents information that points them toward basic rights, as well as working to support and protect the territories. These characteristics educate doers with a project-based mindset. This combined with their significant reach into and deep knowledge of the social dynamics of their neighborhoods usually leads them to create initiatives that promote fundamental rights.

“My first experience in social movement education was at CCJ Recife, where I did a photography course. We worked on the socio-political side, too, using the tools of communication and popular education…And from there, I think in 2012 and 2013, I got stronger on youth policy. We worked a lot on the question of popular education, on the right to the city and to urban mobility and I started getting to know other sectors, other groups of youth…And through that I got even stronger, learning, experiencing, exchanging and conversing with other youth, not just those from the periphery…I woke up, getting a taste for it and becoming who I am today, a youth multiplier and activist.”

Jéssica, Recife

Collectives and Networks

Collectives and networks are the newest formative structures in the territories. They are horizontal by nature, as people group themselves around topics of interest, sometimes temporarily, and begin investigating and producing knowledge or action based on this collective identity. Because of the organic nature of collectives, the same person can be a part of more than one depending on their field of interest and work in the territories.

Out of this space emerge political actors, who are highly-committed to, knowledgeable about and identified with issues of race and gender. This is a direct result of the plural political education at the essence of the residents and the territory. In our research, we found the collectives and networks to be the most fertile spaces for direct political action and activism. It is in the collectives and networks, also, that new ideas for a new, emergent politics are tested.

“We are part of the Journalists from the Peripheries Network. It is extremely important that we use our network, especially now, in such a crucial moment for us, because we don’t have financial resources, we have human resources, we have the ability to mobilize our base. This base includes family, people who live on my street, my neighbors. I felt that when the Journalists from the Peripheries network was created, it gave a boost to all of the collectives that were part of the network. We are still in the process of structuring and articulating, it is very hard to build a network, it is the hardest thing in the world.”

Jéssica, São Paulo

“Our biggest asset is our network. It really is our chief asset, our main tool, our network, breaking down barriers (…) it is about connections between people. Eye contact, truth, differences, it is about things that are hard to name.”

Márcio, São Paulo

Time and the conditions of this moment in history

Three conditions are at the foundation of this moment in history, when doers in the periphery redesign their political roles:

Behavioral Changes: The doers are tapping into interest-based networks, which go beyond class networks. The nature of these new connections builds other repertories, increasing support and strengthening action networks across centers and peripheries.

Technological Changes: Historically, political constructions have taken place in live encounters, such as the Hip Hop Movement in the São Bento Metro Station in São Paulo. Because of technology, especially the internet, actors are organizing with more agility, with more diversity and in larger numbers, building collaboration networks with the strength to advocate for their causes.

“We are becoming more and more technological, we can’t get away from it, and I think we have to utilize, learn to use all of these tools in the best way possible. To build bridges, actually they aren’t even bridges anymore, those things that we open and pass right through, portals, we need to create portals, holograms, and be able to connect, connect with our people. By our people I mean with all of the people who are willing to build this social transformation.”

Evandro, Belo Horizonte

Intersecting Issues: Race and gender, key issues in the society we aim to construct, can be found throughout the political thinking of the doers. They are non-negotiable for political advancement.

“The left doesn’t understand, they wouldn’t get it even if you took an axe and opened up their heads. They repeat class, class, class, class… and you look at that and want to say, are you serious? When a black kid and a white kid go in front of a judge, the judge always assumes that the black kid is poor, helpless and definitely committed the crime. They never think it was the white kid, even if they both came from the same favela. Racism is so bizarre. I have seen cases where the black kid was the leader of the gang, the one who made it all happen, but the person seen in the trial as the leader was the white kid, because, at the end of the day, since when is a black person capable of leading anything?”

Fernanda, Belo Horizonte

“It is possible to coordinate the collectives, they are not all the same, their ways of working are different, sometimes very different, but on some questions – like combating racism, the emphasis on culture and some political reflections – they are aligned and so it is possible to work together.”

Evandro, Belo Horizonte

“It is good to think about the network’s connections with other movements, both throughout the city and in a wider scope. I think there is no turning back on this question, on this form of organization.”

Rose, Belo Horizonte