Initiatives

We mapped more than 400 initiatives connected to political institutions, NGOs, informal collectives or individuals. We selected 100 of those acting in their territories on the issues of independent and alternative media, political participation, collaboration networks, social and cultural movements, environment and social entrepreneurship for in-depth interviews.

#Right to Existence

#Right to Memory, Education and e Culture

#Right to Economy and Living Well

#Right to Political Participation

#Right to Occupy the Power

Belo Horizonte:

“We put someone in government, but we also put on external pressure.” Keep women alive. This is the challenge of those responsible for the Tina Martins House, an independent reference center that gives legal and psychological support and houses women who are in vulnerable situation or were victims of domestic violence. The House was founded in 2016, when women occupied an abandoned public building in Belo Horizonte with the aim of raising awareness about the cases of femicide in Brazil. The occupation, which was supposed to be symbolic, lasted 87 days. “When the federal government asked for the house back, we said, well, you are going to give us something else,” Clarice Filgueiras, one of the people responsible for the project, said. According to her, there was no way that the public authorities could go regress after they had built relationships with other women. Today, the Tina Martins House is a reference for governmental organs, even though it currently has little support from the state. The proposal is to keep pressuring and revealing the possibilites that spring from the real demands of the population.

———————–

Much of what he knows, Flavio Paiva – known as ‘Russo’ – learned on the streets. Born into an evangelical family, he became involved with the punk movement. With the involvement of a family member in drug trafficking he related what happened to Racionais’s rap lyrics to GOG. It was the cue to engage in the Hip Hop movement where he met himself. Rapper and educator active in the movement since 1999, Russo has already participated in different collectives, councils, forums and has applied for being a councilman on the last municipal elections. Three years ago in Ibirité (metropolitan region of BH), he joined young people from the Terra Firme collective, a kind of peripheral incubator with courses, workshops and event production that aims to give visibility to other cultural groups organized by youth in public spaces . People want the youth to be in front of their screens, inside the house, they want to take the youth out of the street, but it is the street that socializes, that makes us human beings. If you take everyone out of the street, you kill humanity, “says Russo, for whom the street is key.

———————–

The politics came to Danusa Carvalho on the 70’s, the age of military dictatorship. She became a teenage activist involved with culture, worked with different artists in Brazil and contributed to the creation of some public policies that we have today. Now she is one of the members of Associação Arebeldia Cultural, an initiative founded by rapper Flavio Renegado in Alto Vera Cruz (a neighborhood in Belo Horizonte) that encourages protagonism, fosters education, professional training and community participation of vulnerability group.

———————–

In the west side of Belo Horizonte, a group of residents resists real estate speculation to preserve the only green area in the neighborhood. Since 2012, there is a project to build two towers with almost 300 apartments, 23 floors and more than 700 parking lot that would be built in the green area of the Jardim América neighborhood. This arrangement was made through an agreement between the City Hall, a construction company and the owners of the land, in default of the protection of the green space as directed by the Master Plan. From then on, the Jardim América movement resists the implementation of the project and seeks to preserve the green area, with several acts of resistance, social mobilization and conflict content, in order to create a park in a block with native forest. The group remains active, joining public councils and audiences. They also are appropriating decision-making tools – in order to preserve that space.

———————–

The year of 1991 mark the beginning Brazil’s redemocratization era. Social movements debate demands of historically neglected Brazilian black population. In Belo Horizonte, a social group related to religions of African matrices draws attention to the matter of considering African subjectivity and religiosity on these political processes. “The system machine is very blind,” says Makota Celinha Gonçalves, national coordinator from Cenarab – National Center for African-Brazilian and Afro-Brazilian Resistance. “The machine say: ‘I can not give you a door because the State is secular’, but it gives to the other [for one hegemonic religion] because historically that other is part of the State.” Cenarab, founded in Minas Gerais’ capital city, is nowadays organized in 18 states and aims to form leaderships to combat religious intolerance, prejudice and discrimination through strengthening these traditional communities and elaborates public policies for its preservation. “Our ancestors had a strategy in our religiosity to guarantee the sacredness of the Orixá. They had a strategy to understand that when they got here, they already had an owner. We need this strategy, “says Father Ricardo de Mouro, one of the directors of the organization.

———————–

“The right to land and housing guaranteed by law needs directa actions as a gear for the urban reform. This is what engage Movimento de Lutas nos Bairros (MLB), in the Belo Horizonte peripheries and other locations. The movement advocates to housing rights and human rights to live in dignity. Formed by thousands of homeless people across the country, MLB believes that the housing crisis is capable of mobilizing thousands of people, pressing the government and calling attention to the issues faced by poor people in big cities. Therefore, the social movement advocates occupation of idle real state as a way to develop the sense of collectivity. “If we do not show in practice that we are different, we do not innovate. the criterion of truth is practice” – Leo Péricles, member of MLB.

———————–

After years below the surface, Belo Horizonte’s Street Carnaval resurges with force in the 2000s, bringing with it a debate about the right to the city and the occupation of public space. And also along with it, diverse identity movements resurge among black people, women and the LGBTQ population. In other spaces, like the universities, these debates also amplify. A series of initiatives arises out of this process. The LGBTQ population organized a unified front potentialize its discourse and amplify its effect, occupying space on municipal and state councils or taking part in legislative mandates. “When you recognize your history and the history of those that are by your side, you are capable of making proposals,” say the members of the LGBTQ Autonomous Front in the city.

———————–

More than 720,000 people are incarcerated in Brazil. 40% of these people are awaiting trial and more than two thirds of them are black. On the other side of the equation, the Judiciary is a white and in large part male class that receives the highest salaries and benefit packages of all public employees. White women and men examining and trying black women and men. Nana Vieira, Ana Paula and other lawyers perceived that the barrier of juridical language, a lack of access to private attorneys, excessive demands on Public Defender’s and the fact that human rights organizations mainly take on emblematic cases perpetuates a process of criminalization of the black and poor population that leaves gaps in their defense. This led them to create Maria Felipa Legal Aid, which provides legal services for low prices. “Not having a lawyer to take their cases keeps people from speaking out, I can’t tell them to speak out unless I can assure that they won’t suffer retaliation,” they explain.

———————–

Where are the black men and women? What spaces do they occupy? The truth is, the more subaltern the job, the more black people occupy it. And the more elevated it is, the more white people occupy it. Based on this discomfort, a group of black activists from Belo Horizonte started the Blacks in Movement Party to fight for space in institutions. The proposal for the party was suspended when they saw that strengthening black women candidates was a more viable path. With that, the party transformed into Black Women in Movement, a collective that works on identifying and strengthening black political subjects who are willing to occupy spaces of power from councils to legislatures. “We are always at the base, always constructing, always mobilizing, always articulating, we are always in this movement, but we never occupied these spaces,” they said. Today, the collective has representatives the Municipal Cultural Council and the State Cultural Council, in universities and in offices of city councilwomen in the Mines Gerais capital. And it is just the beginning of overcoming the scenario of oppression in the country.

———————–

Laura Barroso Gomes´s relation with nature comes from childhood, when she accompanied her grandgather to the fields. This proximity with plant based food itself influenced her choices for graduation in Biological Sciences. But it was in Agroecology that she founded herself. In years working with local farmers in agricultural land reforms project, she was invited to work in the Alternative Tecnologies Exchange Network (REDE).

The organization has 32 years old (the same age as Laura), and arises in the redemocratization of the Country with the articulation of alternative farmers in in the other hand of agribusiness. From these meetings, other organizations emerge from the countryside of Minas Gerais. And REDE begins a project of urban agriculture in the central area of Belo Horizonte – a pioneering initiative that influenced other networks and projects in Brazil, focused on the discussion of public policies on food security and right to the city.

Today, in addition to structuring small families of producers/farmers and generating income, REDE has partners in public positions, presence in local councils, committees and universities. “Slowly, we get there,” says Laura. The theme of healthy food is in the city hall, in the novel … Agroecology is pop, it’s tech, it’s everything!

———————–

Do the civil society organizations you know acts for the emancipation of people or for the maintenance of things as they are?

In 1997, a group of young journalists graduated at PUC-Minas decided to gather participants’ experiences with photography and video to discuss the role of the media in the political formation of youth and educators. This resulted in the Oficina de Imagens, an organization that works to guarantee the rights of children, adolescents and young people of Belo Horizonte using communication and education tools.

“It is a presupposition of the exercise of citizenship to have a critical view of media and critical appropriation of technology,” observes Bernardo Brant, one of the members of Oficina de Imagem, for whom this emancipation will happen with a molecular revolution, starting from small groups.

———————–

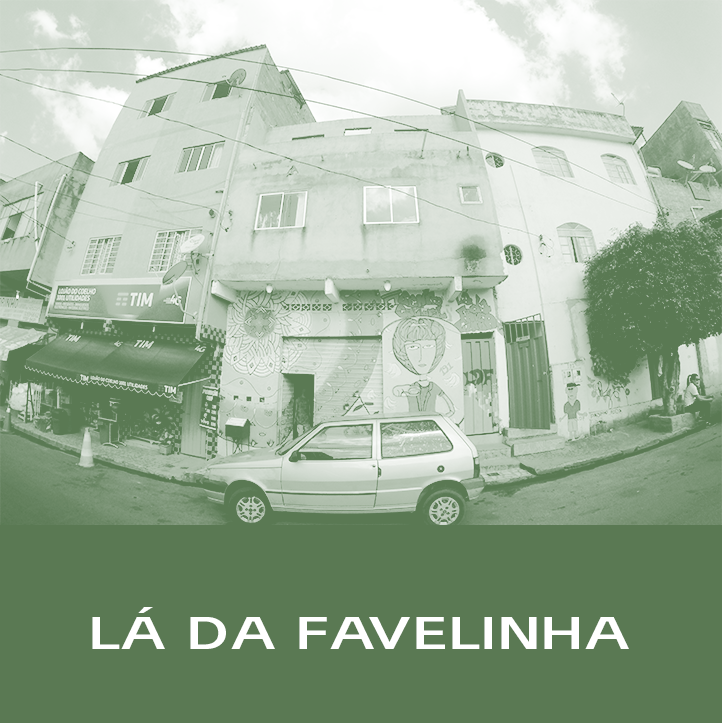

Innovating doesn’t necessarily mean reinventing the wheel, but rather doing what needs to be done with what you have. And this is at the root of Fa.Vela, an accelerator from Minas Gerais. Started in Papagaio hill (center-south of Belo Horizonte), today it stimulates and trains entrepreneurs from other favelas in Belo Horizonte based on the demands and potentialities of each territory. However, even if the population knows that guaranteeing the basics is a big advance, this is not always the case in institutional politics. “The system is not based on pro-activity and the smooth resolution of problems. If a councilperson brings up a demand today, it will have to pass through so much to become a solution. I am afraid the system would swallow me and harden me,” noted João Souza, who founded Fa.Vela alongside Tatiana Silva. On the other hand, movements like the Muitxs, who in 2016 were able to elect two new council women in the capital of Minas Gerais without funding and with a lot of mobilization, help organize these spaces and show that once again the daily challenges indicate the paths to be followed. “Political innovation is autonomous candidacies from and for the favelas and peripheries,” João notes.

———————–

Do you know your roots? In a country where indigenous peoples have been exterminated and enslaved Africans has no rights to memory. It is a privilege.

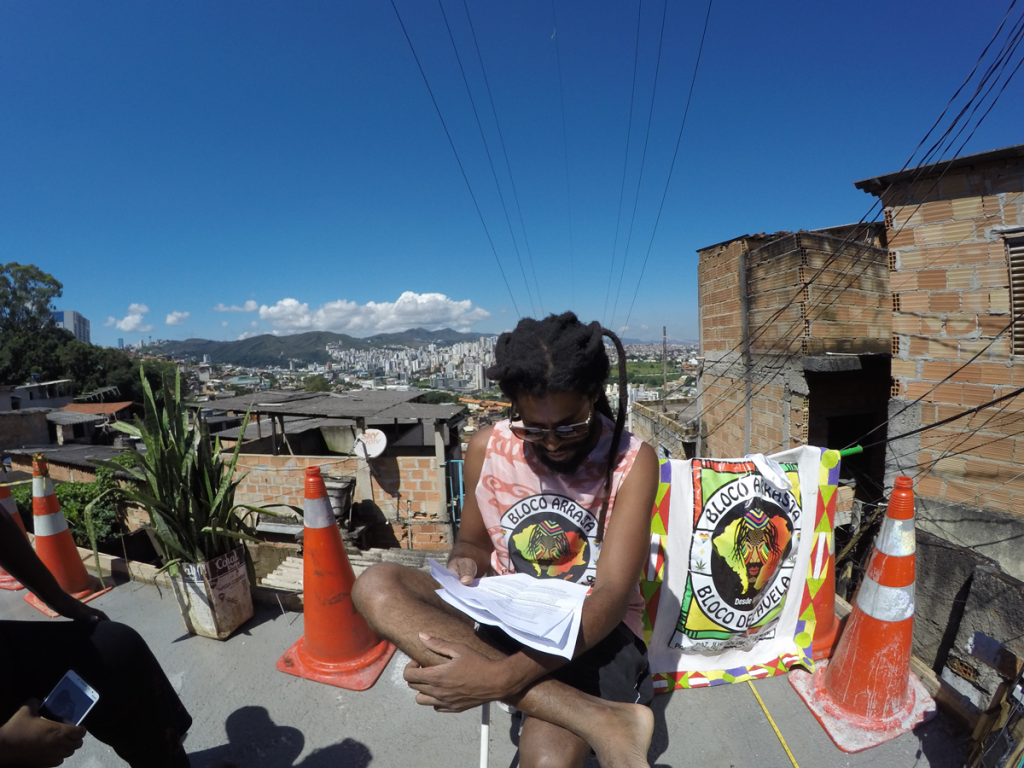

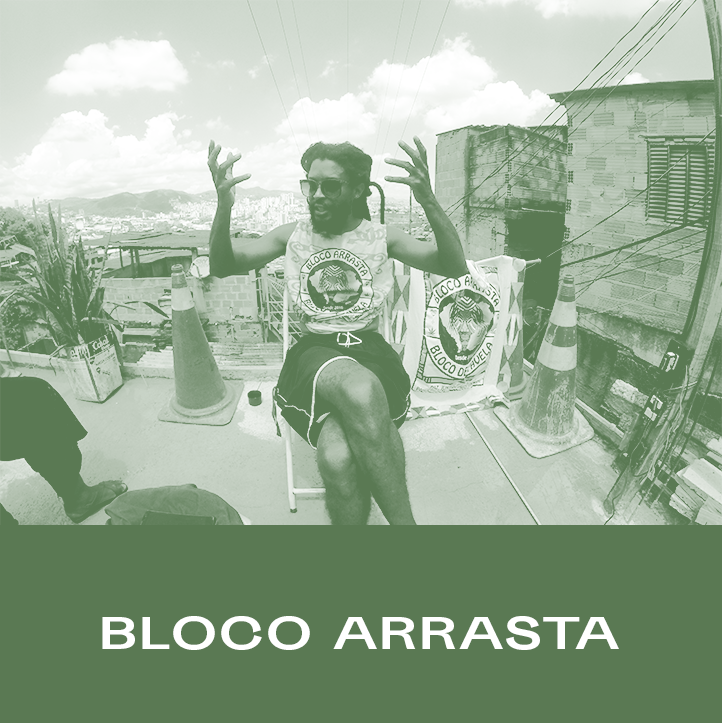

Alvaro Zulu understood the dimension of who is he: a descendant of quilombolas and natives of the region of Governador Valadares, he is one of the thousands of black residents of the towns, agglomerates and favelas of Belo Horizonte. Daughters and sons whose ancestors left their lands in the interior of Minas Gerais towards a better life in the capital, occupied spaces on the shores of the city – like Morro das Pedras, where Zulu lives – and assimilated other cultures.

In mobilizations and wanderings to rescue the memory of his own, he and others created Bloco Arrasta Bloco de Favela, a carnival parade that makes politics day by day from the ancestral rescue and appreciation of Afro-descendants and the recognition. Specially for black women as main axis to solve and overcome historical problems. “Maturity shows me that great things, great transformations take time. It does not just depend on my will. There is a need for awareness, “says Zulu.

———————–

Brasilia:

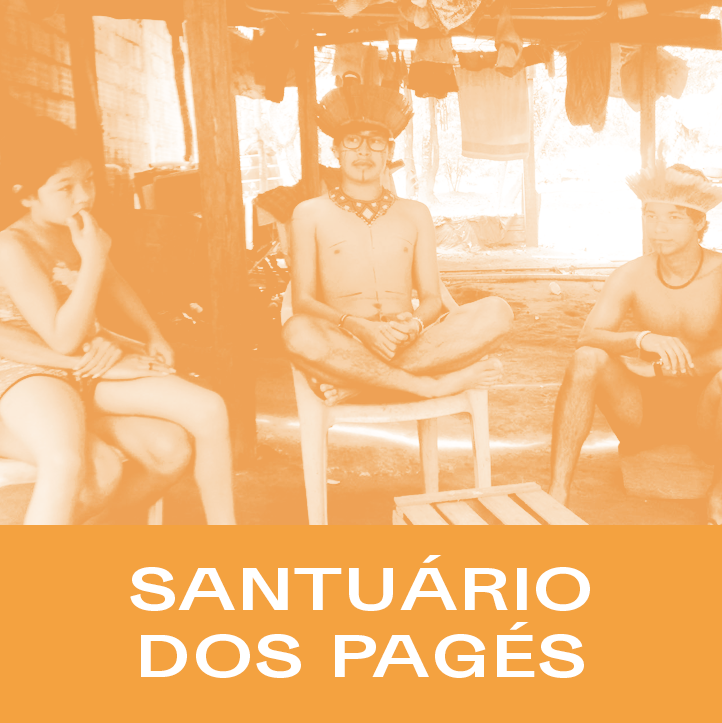

Santuário dos Pajés (Healer’s Sanctuary) is an indigenous territory of three large ethnicities that sits to the northwest of the city of Brasília. It is a territory that resists and fights against unbridled real estate speculation. Its leader, Fetaxá Verissimo, is a young man who inspires his community and us alike!

———————–

Imagine that you are young and lives in the fifth worst city for young people in Brazil. What would you do about it?

Gabriel Fidelis, 25, did not stand still. Born in Brasília, he moved with his parents to Luziânia, a municipality in Goiás that is part of the Entorno – an urban region that covers cities of Goiás and the Federal District that are influenced by the capital.

In 2014, when Luziânia was appointed as a municipality with high youth vulnerability, Gabriel joined other youths to demand a Youth City Council to participate in the city’s decisions, which was created only last year. Meanwhile, they occupied a public area to create a cultural center and Gabriel was a candidate for councilman in the last municipal election. He was not elected, but he also did not give up to occupy these spaces.

“You do not have to be too smart to think about what is the problem that is killing this youth, that is making that youth fade. It’s not very difficult. So the change has to start from the state.” he says.

———————–

2016. Reports of a group rape of a young woman by more than 30 men shock Brazil. In Cidade Ocidental, a municipality of the state of Goiás that surrounds the Federal District, women met to do something beyond their revulsion. That is how the For Us By Us Collective was born. Organized around the idea that women can help other women through emotional support and around the objective of contributing in a positive way to bring about changes in the lives of all. Beyond mutual support, they mobilize effective actions in Cidade Ocidental related to work, services and participation in public hearings and councils.

———————–

Mateus Santana, 26, recognizes himself as a political person since he understood that he was a black resident of the periphery – and what it means: the act of existing and resisting on a daily basis. Born and raised in North Samambaia, satellite city of Brasilia, he is responsible for the O’Beco Cultural. Where daily activities take place, including capoeira, skateboarding, basketball, English and a monthly slam without any governmental support.

Mateus hopes that the space will be recognized as a place of coexistence and consolidation of identities in Taguatinga. Strengthening those who live in the Brazilian ravines. “The black body standing is a political act, because we never know when it will be the next [to fall],” he says. And from his gullet, he believes that the change in the political system will happen when the peripheries and the black people organize themselves to be no longer a base, but protagonists of the process. “There are a lot of people who just need an opportunity, they just need a door, a window, a lock to get in.”

———————–

A big part of the bricks used in the construction of Brasília was made from the potteries of São Sebastião. And it is in reference to the history of this satellite city of federal capital that the Popular Brigades baptized its home. The Cultural Pottery, a collective and collaborative space created to promote human rights, to allow the exchange of ideas and to provide services to the community, as well as cultural activities.

The poet Tiago Xavier began writing in high school and is now the production coordinator of the space, created in early 2017. For him, the challenge is to compete with the TV the time. Therefore, the Cultural Pottery holds saraus in squares and schools, workshops and sambas presentation in open air. More than coexistence, the space allows policy – after all, of the 3 million residents of the Federal District, less than 10% lives in the Plano Piloto. “The one hundred power is us, it’s us already. Now, we just stop being the driver of the powerful and be the powerful ones themselves. ” notes Tiago.

———————–

Lucas Pinheiro is hip hop creator of Distrito Federal, land of exponents like GOG. And today he believes in the mobilization of resources as a political tool for transforming his gully.

Living in Ceilândia, he organizes events since 2009, while still in high school. Afterwards, he organized big parties with friends, worked in NGOs sector in Florianópolis, was a night club promoter in Argentina and when he came back, he created the MUB Produtora – Movimento Undergound de Brasília with six other friends, with the aim of moving the cultural scene of the peripheries of Distrito Federal.

Over time, the producer began to hold workshops to train new agents and to promote local artists as well. “We grew up with friends who were rhyming, we attended the battles from the beginning and we saw there are needs for production and performance that was not just for money,” says Lucas.

———————–

In the middle of Cerrado, the resistance arrives on two wheels. Planned city, with wide and flat avenues, Brasília is known for pedestrian protection and cutting edge cycling. At the same time, it is dangerous for people who use their bicycles to day-to-day tasks – in early 2000s, every week a cyclist was killed on the road.

In 2003, after her husband suffered an accident, journalist Beth Veloso brought together athletes, scholars, engineers, statisticians and pedal groups to think of a more harmonious and less violent city for cyclists. This is how Rodas da Paz was born. An organization that works to change the reality of urban mobility through citizen sensitization and mobilization, social control and influence over public policies.

Since then, Rodas da Paz has articulated a series of public policies for this modality, such as the creation of bike paths throughout the Federal District, and has faced defenders of more space for cars. “A model of a city that we defend is a city that is less dependent on oil,” says sociologist Renata Florentino, who joined the group in 2013 without knowing how to pedal during her doctorate’s research on the legacy of the World Cup in Brazil. “We want a city with a low-carbon transport and at the same time safer for people.”

———————–

In the surroundings of Brasilia, the collective Di Favela lived a contradiction: they worked with elements of hip hop in schools, but a local law criminalized who practiced graffiti (one of these elements).

For this reason, David Marcos and other activists began to take these issues to the district deputies of the Legislative Chamber. More than that, to take parliamentarians and advisers from the offices to know the reality of peripheries and listen to population.

“We have to have space occupancy, you have to argue” David points out. “I know the moment is bleeding, but it’s also a time when so many emerging forces are coming.”

———————–

30 kilometers from the Plano Piloto, the “noble” region of Brasilia, almost half a million people lives in the shadow of stereotypes: Ceilândia, which like many other peripheries in the country is considered a territory of violence. But in Ceilândia em Foco, a community newspaper with a circulation of 10,000 copies per month, the headlines are different. “We have a column called ‘Diva’, for example, where monthly we bring a woman who does something for the community,” explains Pamela Paiva, one of the newspaper’s members.

———————–

Ivanete Silva dos Santos is from Brasília, but she moved with her family to Rondônia in the late 1980s. In the North region, she met the struggles of Chico Mendes, an activist who inspired her political activities. After his death and the return of Ivanete to Brasília, she began to work in unions and went to college. But something was missing: one had to turn to the environmental question, as did Chico Mendes. With no space in trade unionism, Ivanete sought out large NGOs, but he had no room. So she founded her own organization. Today, the Nature House promotes playful activities with children from 9 to 14 years and their families in Ceilândia with the goal of promoting environmental awareness. But Ivanete continues to dream: she wants to extend this project to the whole square, the surroundings of Brasilia.

———————–

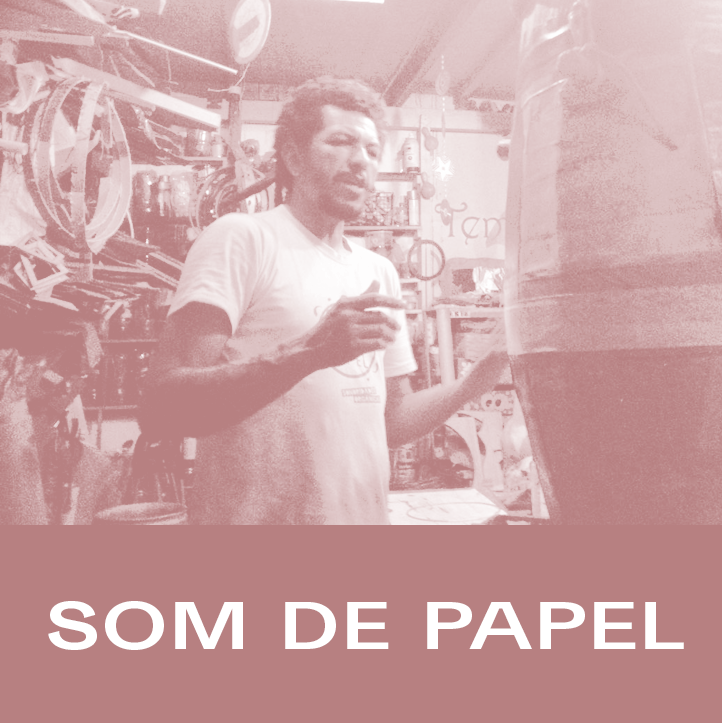

The Bahia’s riverine Juraci Moura has been related to art since childhood, through capoeira. For 33 years living in the Federal District, he was already an adult who went back to art and started studying music. Researching about tambourines, he came to the production of musical instruments with recicle paper and other disposable materials. Thus, the Sound of Paper was born, a musical band that uses percussion instruments made of paper: zabumba, pandeiro, brazilian drum, and others. More than that, it is a group and open space that uses art to discuss environmental issues and political mobilization in region of Taguatinga. “The market is producing enough raw material that turns waste and has no reuse. And people are rebuilding, rebuilding that path, right? ” reflects him, who works with instrument workshops in schools to discuss it. “It’s an spoiler of future, it’s about young people who are going to be interested in doing things differently.”

———————–

What if the place where you live is called Terra da Campanha de Erradicação de Invasões (Land of the Invasion Eradication Campaign free translated)? This is the purpose of Ceilândia, administrative region number 9 (RA-IX) of the Federal District, where 47 years ago thousands of families were taken to help build the federal capital but lives since there in the peripheries. 30 kilometers from the Plano Piloto, Brasilia, the nearly half million inhabitants of this satellite city live in vulnerability/invisibility. In this scenario RAIX emerges, a collective focused on creative peripheral entrepreneurship that produces clothes and provides support to local artists. Territory is the basis of everything. Therefore, the name refers not only to the abbreviation that identifies the administrative region but also indicates the representativeness of Ceilandia to idealizers.

———————–

Visibility to cultural activities of Plano Central. Have a content of quality and reference and, at the same time, be a tool for social reintegration: this is the proposal of Traços Magazine, which highlights the cultural scene of Brasilia in editions that have already become items of collector. Check it out: more than a vehicle of communication, the magazine generates income to people in homeless situation or social vulnerability. For every sell of a magazine which costs R$5, they get R$4.

———————–

Close to power, far from decision making. But not for long. Max Maciel is 35 and lives in Ceilândia, a satellite city of Brasília, the federal capital. He is a social entrepreneur and trained teacher who specializes in race and gender public policy management. He coordinates the Urban Network for Sociocultural Action (RUAS, or STREETS in Portuguese). He has been fighting for change for 17 years in this place within the federal capital’s scenario of inequality. He is a candidate for the district congress in 2018.

———————–

In São Sebastião, satellite city of Brasilia, a community vegetable garden was born in 2004 after the death of a resident by hantavirus, a virus transmitted by rats through urine, feces or saliva. The problem is where there is garbage, has rats. This was the limit for Morro Azul community to gather and act to change this scenario. Take out the trash and rubble in the garden. With only five participants at the beginning, today Horta Girassol involves 30 families. Everyone is integrated: men, women and even children, who help to watering. In addition to raising the self-esteem of the neighbors and serving as therapy for participants, the garden yields results even in the pocket, since buying vegetables at the supermarket is no longer necessary – the crop yields lettuce, chives, coriander, manioc and some fruits. Also, the clean place brought more tranquility in the neighborhood. Crimes have become rare, in opposition to street fights which were frequent. The asphalt and sewage collection have not yet reached periphery of the federal capital, but in a small piece of this neighborhood the neighbors understood what is live in community. For Hosana Alves, who is part of the group and will be running for a legislative position in this year’s elections, initiatives like this are what we need to address and empower. “You have to listen people, work together with people, see the demands,” she says. “People scream, ask, it’s visible for everyone, doesn’t see and listen who doesn’t wanna.”

———————–

Rayne da Silva Soares has been in Expressive Youth for five years. She entered as a student in the audio-visual workshop at the recommendation of a friend. She became an employee and is now on the management team. The program was created in 2007, based on research that showed how violence impacts youth. Its social technology joined health promotion and the creative potential of people aged 18 to 29, who have a unique capacity to generate responses. The organization promotes the collaboration and autonomy of youth through workshops and cultural actions. For Rayane, who is trained in pedagogy and whose first contact with politics happened through the student movement at her school, the political leaders of the future will come out of spaces like this one. “Change is going to come from the state government, but not from the people who are there now. Change will come from the people who are entering the universities, the youth who are doing grassroots work in the communities and occupying those spaces. The people in there now don’t want to change, no they don’t,” she said.

———————–

In the absence of a guarantee of rights to be who we are and express what each one of us feels, the peripheries create their own spaces. And in Ceilândia, located on the borders of Brasilia, a group of women founded Casa Ipê, a cultural center that houses and welcomes cis and trans women, lesbians, bisexuals in their different artistic manifestations. From the experiences and aesthetic experiences, debates, proses, exibitions, saraus and incentive the artistic/cultural production are realized. “Political innovation is give to the all people a voice” says Daniela Vieira, one of the group’s members.

———————–

Recife:

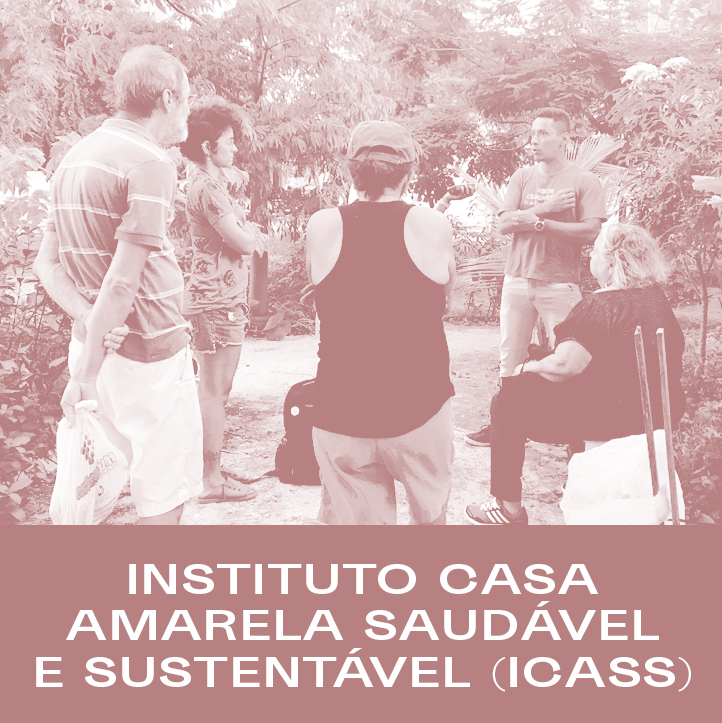

Dulcineia is part of the Casa Amarela Healthy and Sustainable Institute – ICASS, a community association that transformed an empty and idle land into a vegetable garden for the community, as well as mobilizing the actions of residents of the neighborhood focused on healthy and sustainable living practices and habits.

———————–

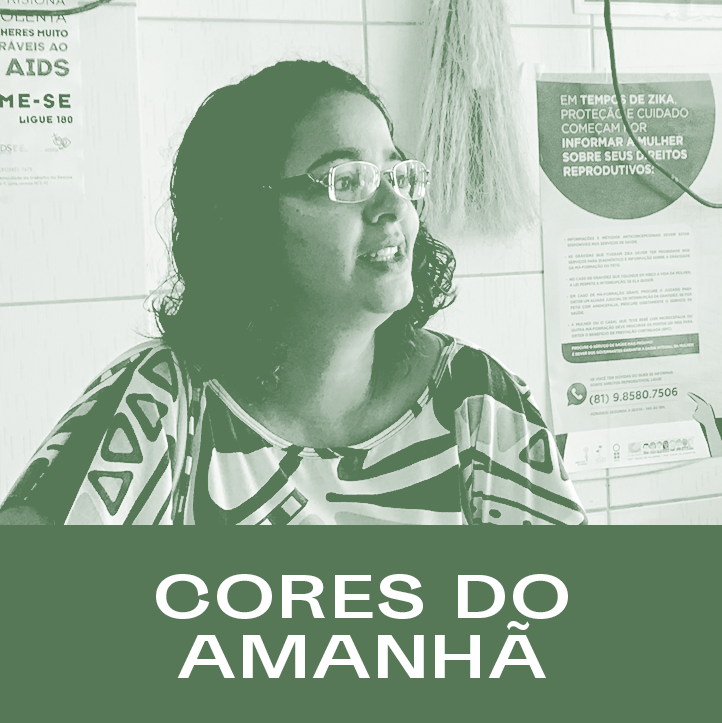

In “Totó” community in Recife, there is a hospital, a prison, a cemetery, but there was only one place for children and young people to learn other horizons. It was then that the Colors of Tomorrow entered, with socio-educational activities, workshops of art, graphite and positive reconstruction of the territory.

———————–

“The big challenge is convincing people that, without them, there is no solution.” 2015. Thousands of black women marched in Brasilia on the 20th of November. And some of the marches out of Recife came back and discussed the importance of keeping the movement strong. And that is how the Pernambuco Black Women’s Network (RMNPE), a non- profit group that fights against racism, chauvinism and for living well without violence. The challenge is not small. Black women are the base of the Brazilian social pyramid, they suffer femicide and from the homicides of black youth, from mass incarceration, from the low alphabetization rates and without formal employment and income. Because of this, the MNNPE didn’t start from scratch, but rather started by recognizing the victories of those that came before, from the Unified Black Movement (MNU), and by bringing together university students and the workers and entrepreneurs from the peripheries who are often underestimated by the white left. “We are a victorious population because we survived and were not eliminated when the state planned and executed its strategies. We value the way that people resist and survive day to day,” they say.

———————–

The poet Patrícia Naia, originally from São Paulo, lives in Recife where she is studying literature in the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE). A former private school student, in that environment at age 13 she perceived that she was part of a minority and that something was not right. “And then I started to write,” she remembers. And she filled notebooks with her writings, typed them onto the computer and then published them on a blog. “Something came to me about writing literature for women, and opening more and more space where women can access literature and share what they write,” she remembers. In August of 2017, she got together with another friend to organize an edition of the São Paulo Slam das Minas in Recife. Slam das Minas, the first poetry competition in Recife led by women, exceeded expectations. More than 300 people showed up in the center of the city. The challenge now is going out to where the girls that participated live, in the peripheries, to write poetry with them and seek effective transformation. Verses are Patrícia’s political tool. “We have a cry inside us and nowhere to yell,” she said.

———————–

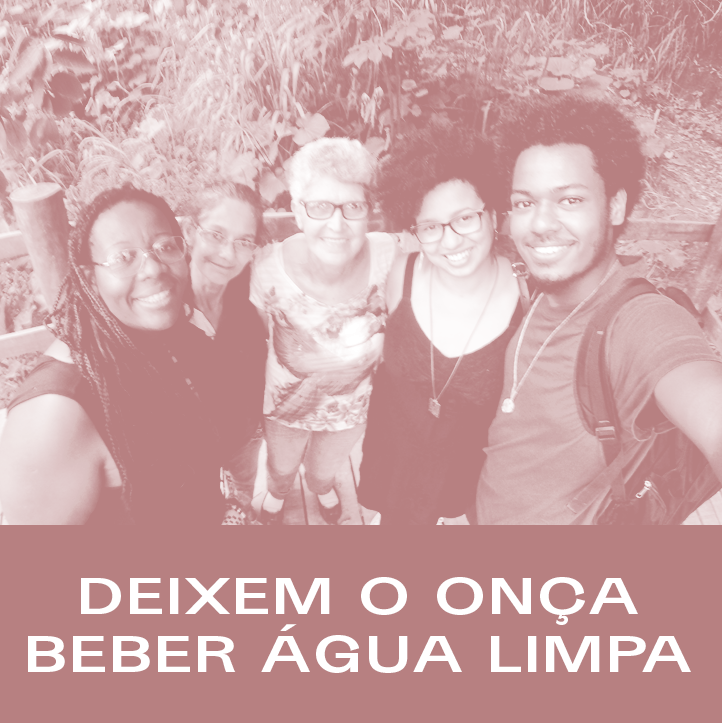

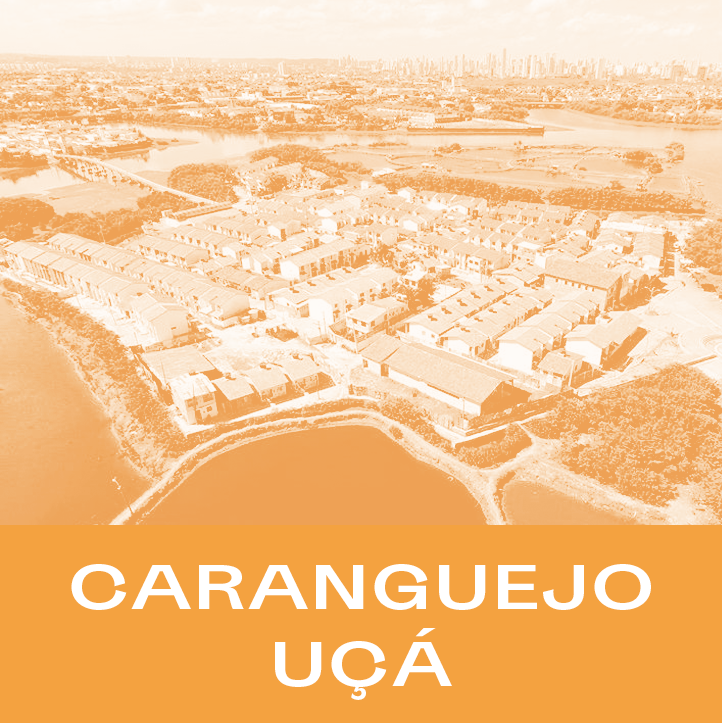

Recife was built on rivers and mangroves, but like many other Brazilian big city also turned back to natural resources. with consequences for those ones who lives in these areas. For this reason, in Ilha de Deus (a community of 5,000 inhabitants), fishing is a form of resistance against real estate speculation, pollution of water and the criminalization of poverty. “100% of the residents live of fishing – if they do not live directly, they already fished one day. Speaking specifically about women, it is much more complex “, explains Eloísa Amaral, who acts as educator in one of the projects of Community Action Caranguejo Uçá. The association was created in 2002 by a group of friends who joined to continue a struggle for survival that has always been carried out by women in the community, such as education and health. So, they created a community radio. With loudspeakers and a microphones in the streest, they have open spaces for discussions about political issues and the importance of organizing themselves to make improvements for the community. Today, in addition to the radio, the Uçá Caranguejo has Jornal da Maré (a monthly program broadcasted by Recife University TV and recorded on Ilha de Deus), the Cine Mocambo (with weekly exibitions), the Maracatu group called Nação da Ilha, the theater group Trilha and the Ciranda de Mulheres, which Eloísa participate. “The great challenge for us is to adapt and mobilize these women, to show that this reality is so difficult for women and for us, women in general, can be minimized when they do not have the support of the others and are aware of your rights”, points out Heloise.

———————–

“We have an opportunity for transformation if we pass the reform in Congress, too.” – Luiza Batista Pereira, Domestic Worker’s Union (Recife) During a sleepless night, Luiza Batista Pereira woke up to politics. She stayed up unable to stop thinking about what she heard from the president of the Domestic Worker’s Union in Recife. “So this means that my retirement, since I did not participate in the struggle, didn’t come so easily?” she asked herself. The daughter of poor farmers, Luiza started work as a domestic employee when she was 9. She did not live her childhood. When she was 36, she got breast cancer and had to spend some time away from her job. That was when she learned about the Union. After that, when she ended a relationship that had lasted 21 years and after almost entering into depression, she decided to go back to school, taking course through union. It was a watershed in my life, how wonderful!” With her children out of the house and having retired at 43 due to disability, Luzia decided to join the Union. And she started to live. She continued her studies, participated in protests in Brasília and seminars and, in 2009, was invited to run for president of the organization. She won and is now serving in her third term. Under her leadership, the Union won many collective victories including protections pregnant domestic workers, 30 days vacation, the right to take holidays off and a constitutional amendment that recognizes her class. Today, at age 62, Luzia knows that there is still much to be done given the regression around the guarantee of rights and the racism, chauvinism and LGBT-phobia that structure society. To her this means occupying spaces of power. “We don’t only fight for us, we also fight beside the minority that is persecuted, the minority in rights.”

———————–

What is the role of the church in debates about racism and chauvinism, for example? “This religious space needs to be shaken up, it needs to go through a seismic shock, even if on a very small scale,” Vanessa Barbosa responds, who was raised in Candomblé until age 11 when she converted to Christianity. After making contact with political discussions at university, where she also reaffirmed her black identity, Vanessa went back to the church to bring up issues that were not on the church’s radar before. To her, Jesus is black and God is a black woman. She searched on social media and found collectives and organizations, spoke with a lot of people until she discovered the Black Evangelical Movement. This national group was started in 2000 and a group formed in Recife last year. It was in this space that Vanessa met Jackson Augusto, who is a Baptist minister. Jackson was born in Comunidade dos Coelhos and lost his father when he was only seven months old. His mother moved to another neighborhood, married another man and suffered domestic violence for eight years. Her church ignored it. “It is very complicated to get outside your bubble, but the reality is much more compelling than the theories or the lies that are told,” he remembers. He started to question why the church did not accept conversations about feminism and did not address racism. Noticing the lack of these discussions and the Christian churches’ silence on or even participation in the colonization and enslavement of black people, Jackson decided to join the Black Evangelical Movement to discuss theology from a black viewpoint. “We are disputing narrative,” he said. The objective is to create a dialogue among social movements, churches and peripheries. The grassroots work consists of visiting and working with small evangelical churches in communities. Those that are known to be the “most conservative” have most readily received the debates. At the end of the day, their reality is black, poor, peripheral and evangelical.

———————–

Adelaide Santos, 20, is in the street working for change. It was echoes of poetry that first called her to the street. After four years participating in theater and African dance classes, her poet friends introduced her to verses and she fell in love with this medium. Joining verses with already-familiar raps, she began relating marginal poetry to her own reality. She spoke of the problems in her house, in the favela, of her friends who were incarcerated and others who had been assassinated. Adelaide needed to speak. She started going to Recital Boca no Trombone, an open mic that happens weekly in a plaza in Água Fria, in the north zone of Recife. She learned about the event previously and started to play an active role last year. “That was when I started to pay attention to the genocide of the black population and realized that I needed to do something,” she said. Today, she uses poetry as a tool for the struggle and an expression that can transform reality.

———————–

Elisângela grew up in Peixinhos, but never had accesses the whole neighborhood while she was a child. That is because in this poor region of Recife, rival gangs competing about territory and restricted the movement of residents. The limit line was a road and you could not cross from one side to the other without authorization. Violence is part of the population’s routine. Nearly 300 youth have been murdered in the last three decades. Elisângela’s brother was one of them. In his time between prison sentences, he did not re-socialized well and eventually another group made an attempt on his life. He was able to escape death, left the state and start over far from his family. Involved with social projects since she was twelve years old, Elisângela knew that she needed to do something. She started with people who was suffering because have lost children to violence, creating Mães da Saudade (Mothers Missing Children) ten years ago. The group supports 60 mothers who have lost their sons to murder. “We help mothers with legal questions, so they can seek for justice against the crime that took their children,” she explains. Beyond that, they host conversation circles, dialogues, and regenerative circles, emotional work to help mothers move through a trauma whose impacts extend far beyond the graveside. And Elisângela knows that her work plays a role in doing significant changes. “There is a serious problem with the denial of rights happening today. The lack of public policies for prevention, which I think is a huge challenge. We have been talking about prevention since we started working. We are going through a moment of significant collapse because the politicians and legal representatives have no commitment to this” – she comments.

———————–

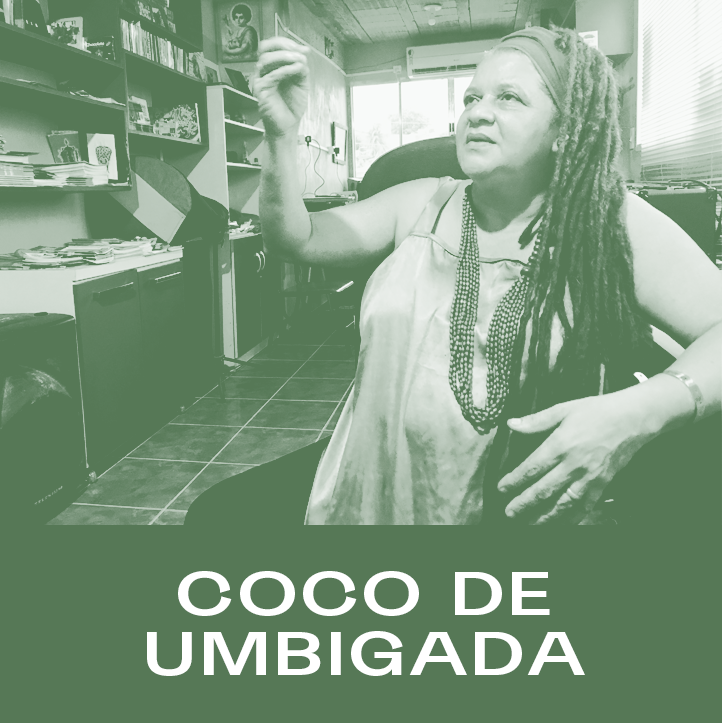

Mãe Beth de Oxum was born, raised and still lives in the Guadalupe neighborhood of Olinda. That is where she does politics. Lalorixá priestiess in a traditional Afro- Brazilian religious space called a terreiro, she has also hosted the Sambada de Coco dance in Guadalupe for the past 20 years. Because of this work, today she also coordinates the Coco de Umbigada Cultural Center. The Center is home to independent media actions, a recording studio, a community radio, a laboratory for independent technologies and citizen innovation and a restaurant. “I am a woman, a mother with many children, some of which I had and others I didn’t, and I am on this front line here, with culture, with religion and with the perspective that we can transform our terreiro into a place that is more like us, blacker, more Afro-Brazilian, that looks like us and includes our perspective on the city,” she said. In a state that kills 60,000 people per year — the majority of whom are black youth — Mãe Beth sees the most pressing challenge as passing public policies that meet the demands of the population. Because of this, in a context of violence, she wants culture to be the protagonist that can renew relationships and preserve symbols. ”It is here in the terreiro that everything happens, that the confrontations happen, rights violations, racism, violence. So it is here that we have to transform, before we can transform the country. We have to transform the place where we live.” Right to existence Elisângela grew up in Peixinhos, but never accessed the whole neighborhood when she was a child. That is because in this poor region of Recife, rival gangs disputed the territory and restricted the movement of residents. The dividing line was a road and you could not cross from one side to the other without authorization. Violence is part of the population’s routine. Nearly 300 youth have been assassinated in the last three decades. Elisângela’s brother was almost one of them. In his time between prison sentences, he did not re-socialize well and eventually another group made an attempt on his life. He was able to escape death, left the state and started over far from his family. Involved with social projects since she was twelve years old, Elisângela knew that she needed to do something. She started with people suffering because they had lost children to violence, creating Mães da Saudade (Mothers Missing Children) ten years ago. The group supports 60 mothers who have lost their sons to homicide. “We help mothers with legal questions, so that they can seek justice for the crime that took their children,” she explains. Beyond that, they host conversation circles, dialogues, and restorative circles that do emotional work to help mothers move through a trauma whose impacts extend far beyond the graveside. And Elisângela knows that her work plays a role in making significant changes. “There is a serious problem with the denial of rights happening today. The lack of policies for prevention, which I think is a huge challenge. We have been talking about prevention since we started working. We are going through a moment of significant collapse because the politicians and legal representatives have no commitment to this,” she comments.

———————–

Cleia Santos is a brave woman. Diarist, artisan, maid, she has done everything in her life. Since 1980s, she has participated in groups that discuss women’s rights, and when she arrived in the Passarinho community (in Olinda) in 1997, she was no different: with other women, she discussed domestic violence in a van. Then they met in other places beyond the van, helded workshops, discussed infrastructure such as access to water, light, housing. The militancy paid off, Cleia’s companions were called to lectures and audiences, and even to an event in Spain. In 2015, inspired by the Ocupe Estelita movement (in the central region of Recife), Cleia created the Ocupe Passarinho – an activist action with participation of several black, feminist and right-to-city movements, in order to fight for the right to land and houses of 5 thousand families who live in the Passarinho community. One of the struggles was for public lighting, nonexistent in that region, which provoked violence against women, such as rape. More than that, today the women of Ocupe Passarinho discuss the reinforcement in transportation, the need for daycare centers, the care in the health posts and the conservation of the river that cuts the neighborhood. “When we make a question about gender, about women’s health, about woman’s body, about her right to come and go, we’re talking about politics” – says Cleia.

———————–

Isabela França is a psychologist, she is 23 years old and engaged with politics came from feminism – first, individually, then collective, as usually happens. “Women have begun to organize first to combat sexism within their own movements,” she says. And in case of the anti-prohibitionist movements, this articulation has expanded by other states. The result of this process is RENFA – National Network of Feminist Antiprohibitionists, with representation in 13 states and based on empowerment of women who use drugs and who are anticlassist, antiracist and antiprohibitionist. In this sense, RENFA also lists mass incarceration due to the drug war, especially of black women living in the peripheries and usually heads of families.

———————–

Food for the rich vs. food for the poor. Does this dichotomy exist? Hamilton Henrique lived in the Menino de Deus community in São Gonçalo (a poor municipality of the Rio metropolitan Region), when he got the opportunity to work in a rich neighborhood in the capital, where the company paid for his lunch. And there he had a completely different experience with food than he was used to at home, much more healthful. It was at that moment that he understood that it didn’t make sense for his family not to have access to this type of food and to have to deal with health problems like diabetes or hypertension, for example. Saladorama emerged out of this reflection. It is a social business that seeks to democratize healthful eating in Brazil as a right and not a privilege. Today, the company discusses solutions for this in many cities around the country, such as Florianopolis, São Luís and Recife.

———————–

On the border between Recife and Olinda was a slaughterhouse. And around this slaughterhouse, communities like Beberibe and Peixinhos were developed, where more than 40 thousand people live. The region is marked by the historic and victorious struggle of local leaders against the installation of a trash transfer station near the river in the 1980s. One of the results is the Boca do Lixo Cultural Movement, which makes direct reference to the historical landmarks: in addition to the fight against garbage, the movement occupied the building of the old slaughterhouse and transformed it into a “hatchery”. It is in this place that Daniel Pereira understood himself as a political subject. He began going to punk shows in the “nascedouro” still adolescent, went to work in the Multicultural Library of Peixinhos created by the movement, went to college and works in the municipal councils of Recife and Olinda. And you, where did you understand yourself as a political subject?

———————–

The neighborhood of Pina has the most expensive square meter in Recife and one of the most expensive in the country. Contradictory, among alleys and alleys hidden behind high-standard buildings, more than 3 thousand families live in stilt houses on the mangrove. And under these conditions, a group of young people used the “pixo” and the graffiti to confront the speculation real estate and to discuss right to the city. From the urban interventions, the collective begins to appear and occupy places of decision making. Today, the Palaffite Cultural Center exchanges idea of equal to equal in spaces of power. “They try to make a hidden policy. But for me, political innovation is community-based. It is a collective mandate. It is a cut of all segments within a collective mandate. It is to listen to minorities and neglected populations within the community, “says Stilo Santos, one of the responsible for the Palaffite, which works on creating a plaque to contest the Legislative Assembly and the House of Representatives in 2018.

———————–

How did you discover that you were a political being? The Afronte Collective discusses ethno- racial questions in public schools and universities in Recife. One of the members is poet and history Master’s student Bell Puã, who grew up in an upper middle class black family. It was in the daily contradictions, in suffering racial discrimination from the stores she visited to the elevators she rode, that she discovered politics.

———————–

How many stereotypes does a neighborhood “dangerous”? Cidicleiton Zumba knows that he is this stereotypes by himself. But he knows local reality, knows that the story is more complex than the newspaper says, and bought the fight to disassemble this version in Tururu, in municipality of Paulista, metropolitan region of Recife. The community was born from the donation of land in the 1980s by the Catholic Church to 600 homeless families. And it was in the parish that many social and political actions developed. There, for example, Zumba gave his B.boy moves in hip hop workshops. And it was here that he had contact with community communication when he wrote for Nois na Fita, the zine of the youth group. As a teenager, he and other colleagues were almost prosecuted in reporting on the non-delivery of medicines by a local health post. “From there, we saw that we had to start with a heavier communication project,” he says. At age 19, Zumba and his friends produced the documentary “Tururu – Justice, Peace and Life”, which seeks to break the stigma of violence and portray the community as a common social space like any other. As a result, the Força Tururu collective, which promotes technical and practical classes on photography, communication and politics, is launched to stimulate the youth to amplify their voices.

———————–

Remember when you had contact with policy? In the case of Jessica Vanessa Santos, a photography course was held at the Communication and Youth Center (CCJRECIFE), an initiative that takes place in Totó (a suburb of Recife), forms young people in communication languages and promotes their participation. discussion and decision-making. Very cool! Jessica appropriated herself so well that she became involved in other collectives, social movements, and youth councils in the county. She has also been a CCJ educator and today, at the age of 22, she is the president of the organization. Ufa! Anything else, Jessica?

———————–

Rio de

Janeiro:

What can we do for our community? In 2001, young people involved in social work at Complexo do Alemão (in the north zone of Rio) gathered and created the Roots in Movement Institute in free translation, which first appeared to work on the environmental issue, to promote sports activities and actions for education and culture. Many have also joined higher education through partnerships between the organization and colleges. From Institute, new local mobilizers have appeared, moving the literary scene, free media and popular participation. Renato Oliveira Lima is one of those who have learned in the coexistence and in the projects of Roots in Movement. And, disbelieving in the change from the state, he believes that it is from initiatives of civil society – such as this – that social transformation must occur.

———————–

Lucia Cabral was born in the countryside of Paraíba in 1967 and was still born to Rio de Janeiro, at the age of six months. In search of a better life, her parents settled in the Complexo do Alemão, where she lived a happy childhood. Lucia’s father dreamed of seeing her as a teacher, while herself wanted to have a school. At age 12, she was already writing letters from Northeasterners to her relatives in the homeland and began to alphabetize some of them. In 1986, he turned his home into a little school and did not stop. Since then, she has worked in different projects as an articulator, educator, coordinator, health promoter … Until in 2008, she started the Educap (Democracy Space of Living Together Learning and Prevention) with other young people in the health area in a room of his own house. The following year, a construction site located in the Field of the sergeant became the new address of the NGO. With a series of partnerships with private companies and public power, today Educap is one of the main organizations that work to guarantee human rights in Complexo do Alemão. And Lucia attributes this to the possibility of having many people participating in the organization’s processes.

———————–

Victor Cantuária, 22, understood himself as a political subject as a teenager. He was part of a dance group in his hometown, Duque de Caxias (in the Baixada Fluminense), in which he was provoked to think about his body as a dancer in the territory. The resumption of its political action occurs when he enters in the college to being an expert in dance. In higher education, founds other black, peripheral and scholarship people who thought about how to give back the acquired knowledge to the territory? – in this case, the Northern Zone of Rio. This is how Favelab was born as an audiovisual collective that today has 18 members and aims to build a narrative about the favelas as opposed of the hegemonic media. With cultural actions, interviews, documentaries, video clips and through direct contact with peripheral cultural artistic practices, Favelab intends to promote different types of artistic performance in urban space.

———————–

Regina Tchelly, a 36-year-old Paraiba, was accustomed to enjoying the food she had left in her homeland. There was plenty left to feed the animals, it was bark that was planted in the yard … But when she moved to Rio de Janeiro and realized that the waste was very common, she saw that she had to act. After working 11 years as a maid, she decided to start her own life project. In the favela of Babilônia, south of the city, she joined a group of women to think about ways to reuse watermelon shells. For Regina, food is a political act because it changes family habits, reflects on waste and the continuous stimulus to consumption instead of reuse. Today, its Favela Orgânica project serves 65 people a week, among children and adults, and aims to change people’s relationship with food, avoid waste, take care of the environment and fight hunger in a practical way, from the Food: Conscious Consumption, Household Composting, Vegetable Gardens and Alternative Gastronomy. “We have a power in the hands of turning without having to draw blood, without having to make people cry,” she says.

———————–

Veruska Delfino lived in the interior of Maranhão until the age of 9, when he moved to Rio de Janeiro. In the South Zone of the city, she began to do theater in an NGO and learned with her teacher Marcus Faustini to link art with social work in the territories. Today, at the age of 29, she works for Rede Redes Para Juventude – an organization created by Faustini in 2011 to empower young people from favelas to turn ideas into intervention projects. “If we do not put these people to be active in this debate, the damage of a generation that we will have soon will be huge” explains Veruska. However, with setbacks happening at ever-increasing speed, the time has come to intensify this action. This is how last year the “Todo Jovem é Rio”, in which 13 young people from different communities in the city, with different profiles and who are already involved in the militancy, receive training in the right to the city, urban mobility, mobilization among others in order to take these debates to those outside the “bubble”. Each young mobilizes four other hosts in his community-be they church, prom, pre-college entrance-and they gather another crowd in their own homes. “Why is it inside the house? Because we want to bring this young closer to the political narrative and not to that old photograph of the politicians that we have” explains Veruska.

———————–

End of the military dictatorship, Rio de Janeiro. At Pedro II College, André Fernandes and his colleagues recreated the student body. This moment marks the political activity of the adolescent, who afterwards joined the Navy as a Marine, left the military career to act in the communities as a missionary of his evangelical church and, in direct work with the press, perceived the demand and the potential of communication for the emancipation of favelas. The dream came to fruition on January 8, 2001, when André and others posted the Favelas News Agency (ANF) website, which today is an organization and also has a printed newspaper with a circulation of 50,000 copies. The ANF aims to stimulate the integration and exchange of information between favelas and improve the quality of life of the population – and this also includes the choice of representatives in the institutional framework. “Political innovation is the conscientization of all the poorest people in whom they must vote,” he points out.

———————–

Samy Brasil already made a social protest with the band Black Music. And in 2013, when they started to do Black Bom, in Pedra do Sal, the port region of Rio, they learned of Cais do Valongo – a veritable cemetery where the bodies of enslaved Africans who did not survive the crossing of the Atlantic were thrown on arrival in more movement of the slave trade. He also met black resistance heroes, became involved in movements and began to participate in seminars … As a result, the ball became the Black Bom Institute, which occupies a space in Lapa and aims to develop black and peripheral enterprises of the state capital.

———————–

“I grew up naturalizing daily violence, not because I wanted to, but because that is what happens to children from favelas. We naturalize a series of things,” she remembers. Later, her family bought a house outside of the favela, where she lived and felt that something was not as it should be. She was the only black child on the street. Even the games were different. Contact with politics — and all of its complicated language — happened later at university, when she started the social sciences course at the Rio de Janeiro State university and became involved with the student movement. “Do you understand what legislators, ministers and judges are saying? And university researchers?” Today, Daniella works to translate the language of the streets into the spaces of power and seeks to guarantee rights the rights that she had access to but that other women and black youth did not. Because of this, she plans to run for state legislature this year. “We can’t take a step back. We are marching, advancing one step at a time.”

———————–

Fala Roça

Fala Roça is a print paper, a channel for communication about daily issues in Rio de Janeiro’s largest favela, Rocinha. Rocinha is located in the South Zone of the city and home to people of mainly Northeastern origin. The person responsible for the paper is 24-year-old native of the community, Michel Silva. The son of general service assistants, Michel has been involved since he was young, often grabbing the paper that his dad brought home from work to keep up to date on the news. Reading the paper one day, he realized that the lifestyle of the people who live on the asphalt is very, very different from the people who live in the favela. With a computer with 256MB of memory and an improvised credential reading “community press,” he began to cover what happened in his neighborhood and to be recognized for his work. From cultural events to the disappearance of the bricklayer Amarildo, Fala Roça is there. And in this election year, he maps out the candidates from favelas and hopes for the election of black youth who are aware of the state of political affairs in the country. “I am hopeful that we will have new candidates, unknown faces, and I think that the role of the media is to show who wants to change politics,” he said. “Transformation comes from people’s resignation.”

———————–

Think of that person who drags half a world behind her, straight from here and there and that makes the stop happen. Thought? In Santa Marta, a favela located in Botafogo (in the rich southern area of Rio de Janeiro), Sheila Souza is one of the people who have this profile. From childhood poor in financial resources but rich in experiences, she works to create possibilities for change where she lives and from what this environment has to offer solutions, aware that the State as it is today will not deliver what we want for free. “What we need is to articulate to empower other ‘Marielles’,” she says, referring to Marielle Franco, a city councilwoman from Rio de Janeiro executed with her driver Anderson Gomes in March 2018. “They can be women, men, but have that strength of real representativeness “. Training tourist, she has accumulated experience since 1992 with community tourism in the favela – what she calls “basic actions”. And since 2010, Brazilidade is a formal social business that promotes connections to help communicate favela culture, its natural, historical and social representations, reducing the invisible barriers between hills and asphalt.

———————–

Coletivo Bonobando brings together artists from various parts of the city of Rio de Janeiro with interventions in the streets, alleys, alleys and also in the conventional theaters. His artistic productions portray his trajectories and relationship with the city, making art and politics walk side by side.

———————–

Rede Umunna is made up of black women who research and promote the presence of black women in political institutions. Umunna’s work involves political training for black women, positioning issues in the public agenda and data-centered research. In this electoral year, Umunna organized the campaign #BlackWomenDecide with the objective of qualifying the debate on the under- representation of black women in Brazilian politics.

———————–

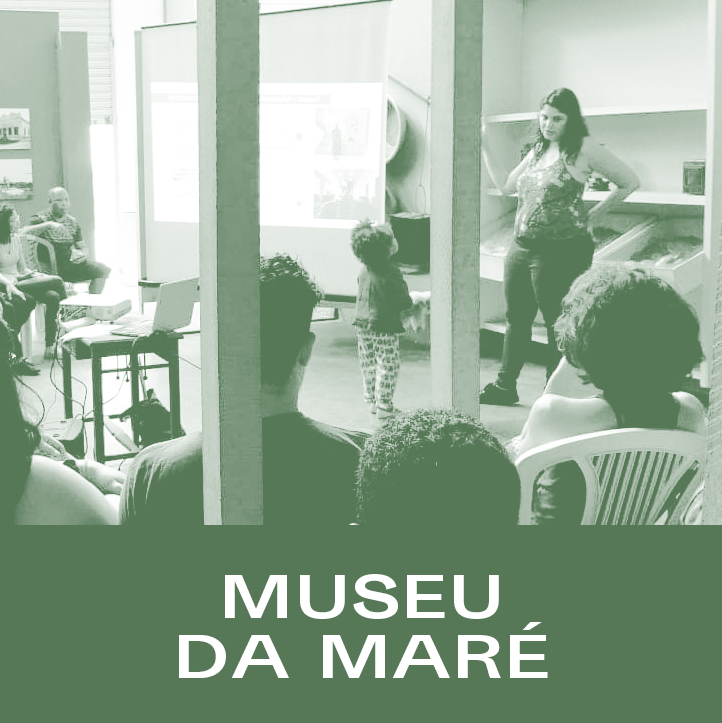

data_labe is a data and narrative laboratory in the Maré favela – Rio de Janeiro. The team is made up of young people from popular territories who produce new narratives through data. At the center of the projects developed is the question of the imaginary built on the city and its inhabitants.

———————–

São Paulo:

Think fast: where is the trans population? Responding to the lack of transgender people, travestis and non-binary people on university committees, a group from PUC (Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo) got together to give classes and prepare this historically marginalized population to occupy the academy. They were able to form a partnership with with the São Paulo Municipal Diversity Reference Center to pay bus fares and with the Educational Action NGO where they were able to host night classes and cultural actions from Monday to Thursday. In addition to the training, the Popular Transformation Course is part of a solidarity network that supports LGBTI+ collectives from the peripheries of the city and individuals looking for a place to live after being kicked out of the homes of their families. For Francisco Aldiney, as long as the state gives no indication of when it will guarantee full rights for trans people, civil society initiatives are important for opening cracks in the system.

———————–

José Soró was born in Mato Grosso. But it was in Perus, in the Northwest of the city of São Paulo, that he became a political subject. In this district located on the banks of the Serra da Cantareira, it had contact with the history of the Queixadas – as the more than 1,400 workers of the Perus Portland Cement Factory, the largest in Latin America, were called, who made and won a strike that lasted seven years and asked for better working conditions. The local historical context influenced the performance of the Catholic Church, the trade union movements and Soró’s own choices in a period still under military dictatorship. After joining a political party, to do higher education, he lived 15 years abroad, returned, married, had children and decided to return to Peru in 2005. When he moved, he found other “Queixadas”: the black youth articulated in Quilombaque Perus, a cultural association to which Soró was invited to contribute. “The whole logic of Quilombaque is to build paths and structures of circulation, to strengthen training. So you form a kid here, but there’s a circuit for him to go through, to assert himself, even this boldness of people thinking that we have to generate income and savings in this circuit, “he says. Today Quilombaque has two cultural occupations, engages in councils, in the struggle for the transformation of the old cement factory into a cultural center and university campus, in the decisions on the Master Plan and in drafting laws such as the Promotion of Culture of Peripheries. “It has to be worth it because it is not a meritorious act, it is a political act and a confrontation.” At the age of 54, with much experience of life and focused on the development of the territory, Soró takes up again what the Queixadas preached: it is necessary to have permanent firmness. “The only chance for you to face lethality is for local people to exist.”

———————–

Vinicius de Morais thinks politics from permaculture, a concept that values the patterns and characteristics of natural ecosystems applied to agriculture and the use of resources – something truly sustainable. And the way to that understanding is long. Vinicius remembers his grandmother, born in an indigenous tribe in Itaim Paulista (east side of São Paulo), midwife and benzedeira, who always brought the traditional knowledge to solve day to day issues. Among children, weddings, comings and goings to Ribeirão Preto, Vinicius also drew from memory the teachings of the matriarch. In the agribusiness capital, he began to question the model of food production and how indigenous peoples point to another, more harmonious path. It was in the interior that he met the Landless Movement (MST) and initiatives such as agroforestry. He moved to Alto Paraíso de Goiás and, back to the east side of São Paulo, joined an environmental education project in a land provided by the Housing Development Company (CDHU), where he finally managed to extrapolate the contents to talk about permaculture, solidarity economy and development. The Point of Sustainable Social-Environmental Culture emerges from these paths. Today, it involves women from the community and generates income through the provision of various services. Vinicius also works in the Municipal Council for the Environment and works for the reopening of a community radio in Itaim Paulista – all within the principles of permaculture.

———————–

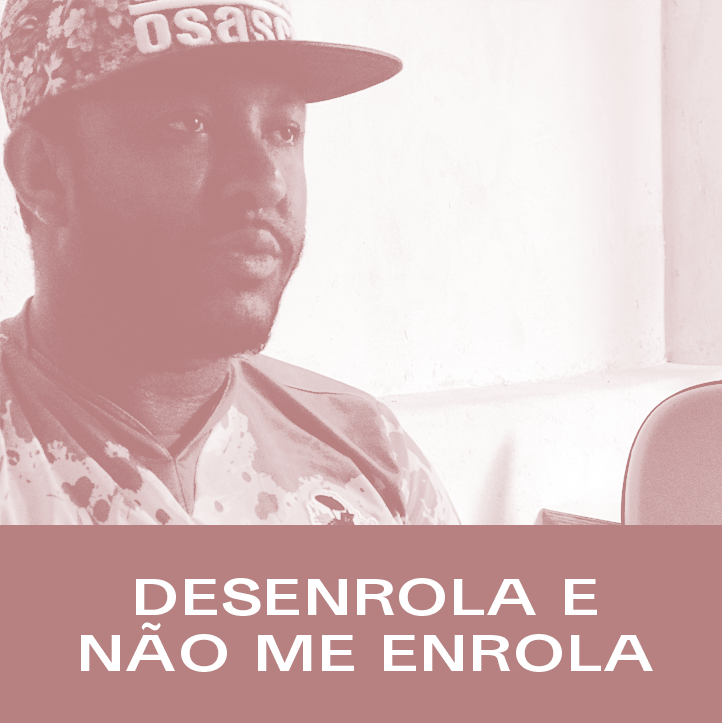

The first time that Ronaldo Matos took action to transform his reality was when he understood that information has the power to help people change their lives. This happened first when he was a child, but hit home when Ronaldo was an adult and worked in the corporate sector. Concern pushed him to create Desenrola e Não Me Enrola, a communication collective in Jardim Ângela (SP) that portrays what is happening socially and culturally in peripheries of São Paulo. Beyond content production, the collective also organizes “You, Reporter from the Periphery” an education and communication project for youth and the “São Paulo Periphery Writers Congress” which highlights literature and authors from the periphery. Since 2017, it has managed the “M’Boi Mirim Center for Media and Popular Communication,” which is a community space that has a collaborative office, a multimedia photography and video studio, an auditorium for speeches and workshops and a newsroom for the portal. The collective does politics, specifically supporting people who are seeking information to act politically. “For me, the main characteristics of people who do politics today are openness to encounters, to understanding other narratives, other contexts, acquiring new knowledges,” Ronaldo says.

———————–

What to do when the state does not fulfill its obligation to foster culture? In the case of the Instituto Pombas Urbanas, the way was to occupy this space. The institute was created in September of 2002 by the group of theater of the same name and that is the result of a project idealized by the peruvian actor Lino Rojas. The performance always happened in the East Zone, with Theater in Community, initially in São Miguel Paulista – an old quarter, and strongly marked by the northeastern migration. In the search for a space of its own, in 2004, the “Pombas Urbanas” found an abandoned shed in Tiradentes City, where a supermarket used to work. It is in this ruined space, without ceiling, that the group begins a work with the community for projects of artistic formation and of public. Revitalized, the “Centro Cultural Arte em Construção” became an autonomous space that houses events, shows and courses, as well as a community library with 10,000 titles. Managed by the community itself, the space also houses three groups that are the fruit of its occupation – Filhos da Dita Teatral Nucleus, Cia Teatral Aos Quatro Ventos and Teatro Palombar Theater Group – and receives more than 25,000 people a year. “Our political action is very much linked to making daily to give life. It is not something that came from an ideological place, an ideological formation is not, it is a practice, “explains Adriano Paes, 42, one of the articulators of space.

———————–

Peripheries of São Paulo. 1990s. With homicide rates higher than warring nations, Jardim Ângela is “elected” the most dangerous place in the world. It is in this territory that Márcio Teixeira, the “Macarrão”, grows with blood in the eyes and attentive ears in which they said Racionais, Facção Central and other exponents of rap that made the head of the student of the time. From an isolated ravine in the extreme south of the state capital, he crossed the bridges to study, work, meet people from other peripheries and better understand why this is so. And back to Angela, banged DJ Bola and other parties, who created hip hop events. We ran to secure equipment for rap, break and graffiti presentations, had a lot of negotiation – whether to avoid gang-cracking or avoiding problems with the police. “We just wanted to have fun in peace, but it was seen mediating conflicts,” recalls Macarrão. From this experience, A Banca, a social cultural producer that promotes artists, organizes hip hop events and workshops in schools and garages in the region, and discusses solutions to the problems of the bust through entrepreneurship. And he takes this knowledge also to the richer parts of the city, to try to change the structures that perpetuate inequalities. More than cultural actions, A Banca creates bridges.

———————–

Is being an entrepreneur a political act? Straight out of Jardim São Luís, in the extreme south of São Paulo, Luís Henrique Coelho and Jennifer Rodrigues tell it like it is: disputing and occupying space is the way to prioritize what populations from the periphery demand and to provoke necessary changes. That is why they created Empreende Aí, which capacitates, accompanies and seeks financial support for youth to create their own businesses and generate income.

———————–

Jardim Brazil, Extreme North of São Paulo, next to Serra da Cantareira: the middle of the Earth is here. Better yet, “Casa do meio do mundo” (House in the Middle of Earth), a collective space for cultural agents, communication professionals and researchers from peripheries interested in social transformation with a hyperlocal perspective. Ingrid Felix and Jesus dos Santos, members of the collective, understand what residents want. Activists from cultural movement of periphery, they assisted to write a law for cultural support on peripheries, based on the human development index in São Paulo ‘ghettos’; This law, passed in 2016, directs resources for these organizations in regions tending to receive less from the government. This street experience, in the struggle, feeds the ‘Casa no meio do mundo’. Over there, political leaders from comunity get training to continue on the front lines, disputing resources from the municipal budget. They work to strengthen local development with an emphasis on care and horizontality. “Beforehand, representatives far away from us spoke for us. Now we are speaking for ourselves” Jesus notes.

———————–

Since 2012, Liga do Funk (Funk League) has used the music genre most often heard by the youth from favelas as a political tool and social inclusion. In addition to forming new MCs, DJs, dancers and producers, the organization frequently promotes debates on Hip Hop, women’s rights and the LGBT population, on drugs regularization among many others.

———————–

In order to keep alive the culture of ‘samba’, the most popular brazilian expression, the Samba Autêntico Cultural Institute works for research, cultivate and spread the samba culture of São Paulo, showing its roots for everyone and mostly to experience the political function of this musical genre.

———————–

Imargem is more than a junction of the words image and margin. It is a multidisciplinary initiative created in 2006 on the south side of São Paulo on the shore of the Billings reservoir in the Grajaú district. They proposes a careful look at the periphery populated landscape, fostering thinking and acting face on potentialities and problems of our society, from the margin to centrality of the city, widening the eyes and sharpen the sensibilities of all to the urban space.

———————–

See more: ![]()

![]()

Periferia em Movimento is a communication collective made from and to the peripheries made of journalists from the extreme south of São Paulo. Their mission is identifying, recognizing and promoting initiatives of social activists, cultural producers and other agents of social transformation of the peripheries.

———————–

See more: ![]()

![]()

The project “Preta, vem de bike!” is a action by La Frida (black cycloactivism) that unites bike advocacy with social inclusion, ethnic equity and gender equity. Aims to take urban mobility, beyond the coast, to the peripheries and quilombola communities. They are bike lessons for periphery girls and quilombola women, stimulating the feminine representativeness in urban mobility, increasing voices of black women and occupying spaces, the bike being an instrument of empowerment in the society. “Preta, vem de bike” has the goal to envolve bike beyond mobility, including the access to basic rights, healing processes, self esteem and dreams.

———————–

Veja mais em: ![]()

![]()